News & Analysis

What is the Future of Arbitration in Kenya?

Published

2 years agoon

By

Admin

By Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD (Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Policy Advisor, Natural Resources Lawyer and Dispute Resolution Expert from Kenya), Winner of Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021, ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021*

One thing is beyond question: there is a bright future for arbitration and alternative dispute resolution in Kenya and around the world. This is due to the renewed quest for legal systems the world over to finding new and more effective ways of providing these services to meet the needs of people in an even greater array of human transactions. In Kenya, under Article 159 (2)(c) of the Constitution, the judiciary is required to promote the use of alternative forms of dispute resolution including reconciliation, mediation, arbitration and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms. The Constitution also provides that national laws should provide for the procedures to be followed in settling intergovernmental disputes by alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, including negotiation, mediation and arbitration. It seems that the future of Alternative Dispute Resolution in Kenya is bright and really promising in bringing about a society where disputes are disposed of more expeditiously and at lower costs.

One of the increased approaches to arbitration entails court-ordered arbitration. This form of arbitration which is taking root around the world requires parties to present their dispute to an arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators for resolution. When parties are ordered to arbitrate, however, they face the possibility of losing their day in court unless they first opt for arbitration. Presently, international arbitration in Kenya has picked up. The Nairobi Centre for International Arbitration Act (No. 26 of 2013) establishes the Nairobi Centre for International Arbitration (NCIA) whose functions include, inter alia, to promote, facilitate and encourage the conduct of international commercial arbitration in accordance with the Act; to administer domestic and international arbitrations as well as alternative dispute resolution techniques under its auspices; to ensure that arbitration is reserved as the dispute resolution process of choice; and, to develop rules encompassing conciliation and mediation processes.

NCIA is administered by a Board of Directors as provided for under the Act. There is also an Arbitral Court established under the Act, which court has exclusive original and appellate jurisdiction to hear matters that are referred to it under the Act. Its capacity to handle domestic and international arbitration requires to be constantly improved, and it can only be hoped that this potential will be exploited to its maximum in the years to come so as to prominently place Kenya on the global map of international arbitration. Kenya also has qualified and experienced arbitrators who are arbitrating commercial disputes around Africa. Indeed, following the revival of the East African Community and the expansion of regional trade, the possibility of Nairobi becoming a regional centre for arbitration is very high. Therefore, the prospects of international commercial arbitration in Kenya are really promising. The use of arbitration is therefore critical in Kenya in settlement of disputes, not only in the commercial set up but also in settling intergovernmental disputes between the County government and the national government, as envisaged in Article 189 of the Constitution.

Since it is a consensual, flexible, cost-effective, private and expeditious process, the role of arbitration in an emerging economy like Kenya cannot be gainsaid. The use of arbitration in commercial and all other disputes where it is amenable is thus the way of the future. With the enactment of the Constitution of Kenya in 2010, there is no doubt that a bright future lies ahead for arbitration and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in Kenya. This is so because the Constitution now obligates the judiciary, in its pursuit of expeditious resolution of disputes and enhanced access to justice, to promote the use of alternative forms of dispute resolution including reconciliation, mediation, arbitration and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms.

Recognising arbitration as one of the main conflict resolution mechanisms in Kenya is, thus, encouraging. Its status has been elevated. Its applicability also to a wide array of disputes will thus be seen in the near future. Previously, the idea of access to justice in Kenya had been equated to litigation which for a long time has been the predominant mechanism though which parties enforce their rights. However, there has been a paradigm shift under the Constitution of Kenya, 2010 which mandates courts and tribunals while exercising judicial authority to promote alternative forms of dispute resolution including reconciliation, mediation, arbitration and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms.

Arbitration, thus, enjoys constitutional recognition in Kenya pursuant to this provision. Courts have slowly embraced this shift and acknowledged the different aspects of what constitutes access to justice as was captured by the High Court in the case of Dry Associates Limited v Capital Markets Authority & Another Interested Party Crown Berger (K) Ltd (2012) eKLR in the following words:

[110] “Access to justice is a broad concept that defies easy definition. It includes the enshrinement of rights in the law; awareness of and understanding of the law; easy availability of information pertinent to one’s rights; equal right to the protection of those rights by the law enforcement agencies; easy access to the justice system particularly the formal adjudicatory processes; availability of physical legal infrastructure; affordability of legal services; provision of a conducive environment within the judicial system; expeditious disposal of cases and enforcement of judicial decisions without delay.”

While the High Court in the above case seemed to give prominence to the formal adjudicatory processes, ADR has been embraced by the courts. In addition, while the effectiveness of ADR processes under the guidance and direction of courts may have its pros and cons (which are beyond the scope of the current discussion), it is indeed a step in the right direction in making access to justice accessible by the public. The scope for the application of arbitration has also been extensively widened with the Constitution now providing that various national laws should provide for the procedures to be followed in settling disputes by alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, including negotiation, mediation and arbitration.

*This article is an extract from the Book: Settling Disputes Through Arbitration in Kenya, 4th Edition (Chapter 12), Glenwood Publishers, Nairobi, 2022 by Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya). Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a Senior Lecturer of Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law and The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP). He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Dr. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Africa Trustee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates. Dr. Muigua is recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2022.

References

Muigua, K., Settling Disputes Through Arbitration in Kenya, 4th Edition, Glenwood Publishers, Nairobi, 2022, p. 345 to 349.

You may like

-

The Challenges in Actualizing Sustainable Blue Economy in Kenya

-

The Meaning of Blue Economy in Kenyan Context

-

The Meaning of Environmental Pollution in Kenya

-

Overview of Human Right to Clean, Safe and Healthy Environment

-

What Issues are Required for ESG Reporting in Kenya?

-

Value Creation as an ESG Management Strategy

News & Analysis

Way Forward in Applying Collaborative Approaches Towards Conflict Management

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 24, 2024By

Admin

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is the Academic Champion of ADR 2024, the African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, the African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) and Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, March 2024)*

It is necessary to embrace and utilize collaborative approaches in managing conflicts. These techniques include mediation, negotiation, and facilitation. These mechanisms are effective in managing conflicts since they encourage parties to embrace and address disagreements through empathy and listening towards mutually beneficial solutions. Collaborative approaches also have the potential to preserve relationships, build trust, and promote long term positive change. They also ensure a win-win solution is found so that everyone is satisfied which creates the condition for peace and sustainability. These approaches are therefore ideal in managing conflicts. It is therefore important to embrace collaborative approaches in order to ensure effective management of conflicts.

In addition, it is necessary for third parties including mediators and facilitators to develop their skills and techniques in order to enhance the effectiveness of collaborative approaches towards conflict management. For example, it has correctly been observed that mediators and facilitators should listen actively and empathetically in order to assist parties to collaborate towards managing their dispute. Therefore, when a dispute arises, the first step should involve listening to all parties involved with an open mind and without judgment. This should entail active listening, which means paying attention to both verbal and nonverbal cues and acknowledging the emotions and perceptions involved.

It has been observed that by listening empathetically, a third party such as a mediator of facilitator can understand each person’s perspective and start to build a foundation for resolving the conflict through collaboration. In addition, while collaborating towards conflict management, it is necessary to encourage and help parties to focus on interests and not positions. It has been pointed out that focusing positions can result in a standstill which can delay or even defeat the conflict management process. However, by identifying and addressing the underlying interests parties can find common ground and collaborate towards coming up with creative solutions towards their conflict.

Mediators and facilitators should also assist parties to look for areas of agreement or shared goals. Identifying a common ground can build momentum and create a positive environment for resolving the conflict. Further, in order to ensure the effectiveness of collaborative approaches in conflict management, it is necessary to build strong collaboration. It has been asserted that strong collaboration can be achieved by establishing a shared purpose, cultivating trust among parties, encouraging active participation by all parties, and promoting effective communication.

Strong collaboration enables parties to develop trust between and among themselves and strengthen communication channels between the various parties. It also helps to generate inclusive solutions that arise from wider stakeholders’ views. Therefore while applying collaborative approaches, it is necessary for parties to foster strong collaboration by identifying common goals, building trust, ensuring that all stakeholders are involved, and communicating effectively in order to come up with win-win outcomes.

Finally, while embracing collaborative approaches in conflict management, it is necessary for parties to consider seeking help from third parties if need arises. For example, negotiation is always the first point of call whenever a conflict arises whereby parties attempt to manage their conflict without the involvement of third parties. It has been described as the most effective collaborative approach towards conflict management since it starts with an understanding by both parties that they must search for solutions that satisfy everyone.

It enables parties to a dispute to come together to openly discuss the issue causing tension, actively listen to each other, and come up with mutually satisfactory solutions. However, it has been correctly observed that negotiation may fail especially if the conflict is particularly complex or involves multiple parties due to challenges in collaborating. In such circumstances, where negotiation fails, parties should consider resorting to other collaborative approaches such as mediation and facilitation where they attempt to manage the conflict with the help of a third party. A mediator or facilitator can assist parties to collaborate and continue with the negotiations and ultimately break the deadlock.

*This is an extract from Kenya’s First Clean and Healthy Environment Book: Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya and Academic Champion of ADR 2024. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2024 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Bercovitch. J., ‘Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations: A Framework for Analysis.’ Available at https://ocd.lcwu.edu.pk/cfiles/International%20Relations/EC/IR403/Conflict.ConflictManagementinOrga nizations.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Bercovitch. J., ‘Mediation Success or Failure: A Search for the Elusive Criteria.’ Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 7, p 289.

Bloomfield. D., ‘Towards Complementarity in Conflict Management: Resolution and Settlement in Northern Ireland,’ Journal of Peace Research., Volume 32, Issue 2.

Burrell. B., ‘The Five Conflict Styles’ Available at https://web.mit.edu/collaboration/mainsite/ modules/module1/1.11.5.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Demmers. J., ‘Theories of Violent Conflict: An Introduction’ (Routledge, New York, 2012).

Diana. M., ‘From Conflict to Collaboration’ Available at https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/conflict-collaboration-beyond-projectsuccess-1899 (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization., ‘Collaborative Conflict Management for Enhanced National Forest Programmes (NFPs)’ Available at https://www.fao.org/3/i2604e/i2604e00.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

International Organization for Peace Building., ‘Natural Resources and Conflict: A Path to Mediation.’ Available at https://www.interpeace.org/2015/11/naturalresources-and-conflict-a-path-to-mediation/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Isenhart. M.W., & Spangle. M., ‘Summary of “Collaborative Approaches to Resolving Conflict” ‘ Available at https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/isenhart-collaborative (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Kaushal. R., & Kwantes. C., ‘The Role of Culture and Personality in Choice of Conflict Management Strategy.’ International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (2006) 579– 603.

Leeds. C.A., ‘Managing Conflicts across Cultures: Challenges to Practitioners.’ International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 2, No. 2, 1997.

May. E., ‘Collaborating Conflict Style Explained In 4 Minutes’ Available at https://www.niagara institute.com/blog/collaborating-conflict-style/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Miroslavov. M., ‘Mastering the Collaborating Conflict Style In 2024’ Available at https://www.officernd.com/blog/collaborating-conflictstyle/#:~:text=It’s%20one%20of%20the%20strat egies,their%20underlying%20needs %20and%20interests. (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K & Kariuki. F., ‘ADR, Access to Justice and Development in Kenya.’ Available at http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ADR-access-tojustice-and-development-inKenyaRevised-version-of-20.10.14.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution and Access to Justice in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2015.

Muigua. K., ‘Reframing Conflict Management in the East African Community: Moving from Alternative to ‘Appropriate’ Dispute Resolution.’ Available at https://kmco.co.ke/wpcontent/uploads/2023/06/ Reframing-ConflictManagement-in-the-East-African-CommunityMoving-from-Alternative-toAppropriate-Dispute-Resolution (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Resolving Conflicts through Mediation in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2nd Edition., 2017.

Quain. S., ‘The Advantages & Disadvantages of Collaborating Conflict Management’ Available at https://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantagesdisadvantages-collaborating-conflict-management-36052.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Samuel. A., ‘Is the Collaborative Style of Conflict Management the Best Approach?’ Available at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/collaborative-style-conflictmanagement-best-approach-samuel-ansah (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

United Nations., ‘Land and Conflict’ Available at https://www.un.org/en/landnatural-resources-conflict/pdfs/GN_ExeS_Land%20and%20Conflict.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Weiss. J., & Hughes. J., ‘Want Collaboration?: Accept—and Actively Manage— Conflict’ Available at https://hbr.org/2005/03/want-collaboration-accept-andactively-manage-conflict (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

News & Analysis

Opportunities and Challenges of Collaborative Conflict Management

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 24, 2024By

Admin

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is the Academic Champion of ADR 2024, the African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, the African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) and Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, March 2024)*

One of the key collaborative approaches that can be applied in conflict management is mediation. Mediation has been defined as a method of conflict management where conflicting parties gather to seek solutions to the conflict, with the assistance of a third party who facilitates discussions and the flow of information, and thus aiding in the process of reaching an agreement.

Mediation is usually a continuation of the negotiation process since it arises where parties to a conflict have attempted negotiations, but have reached a deadlock. Parties therefore involve a third party known as a mediator to assist them continue with the negotiations and ultimately break the deadlock. A mediator does not have the power to impose a solution upon the parties but rather facilitates communication, promotes understanding, focuses the parties on their interests, and uses creative problem solving to enable the parties to reach their own agreement.

Some of the core values and principles guiding mediation as a collaborative approach towards conflict management include impartiality, empathy, valued reputation, and confidentiality. It has also been pointed out that mediation has certain attributes which include informality, flexibility, efficiency, confidentiality, party autonomy and the ability to promote expeditious and cost effective management of dispute which makes it an ideal mechanism for managing disputes.

Mediation is an effective mechanism that can foster collaboration due to its potential to build peace and bring people together, binding them towards a common goal. Mediation can also foster effective management of conflicts by building consensus and collaboration. It has been argued that mediation can enhance collaboration towards conflict management due to its emphasis on the need for a mediator who listen to the wants, needs, fears, and concerns of all sides. Therefore, for mediation to be effective in fostering collaboration, the approach must be mild and non-confrontational because the goal is to make all parties feel comfortable expressing their views and opinions.

Another key collaborative approach towards conflict management is negotiation. It has been defined as an informal process that involves parties to a conflict meeting to identify and discuss the issues at hand so as to arrive at a mutually acceptable solution without the help of a third party. Negotiation is one of the most fundamental methods of managing conflicts which offers parties maximum control over the process66. It aims at harmonizing the interests of the parties concerned amicably. Negotiation has been described as the process that creates and fuels collaboration.

Negotiation fosters collaboration since it involves all parties sitting down together, talking through the conflict and working towards a solution together. Negotiation has been described as the most effective collaborative approach towards conflict management since it starts with an understanding by both parties that they must search for solutions that satisfy everyone. It enables parties to a dispute to come together to openly discuss the issue causing tension, actively listen to each other, and come up with mutually satisfactory solutions. If negotiation fails, parties may resort to other collaborative approaches such as mediation and facilitation where they attempt to manage the conflict with the help of a third party.

Facilitation is another key collaborative approach towards conflict management. Facilitation entails a third party known as a facilitator who helps parties to a conflict to understand their common objectives and achieve them without while remaining objective in the discussion. A facilitator assists conflicting parties in achieving consensus on any disagreements so that they have a strong basis for future action.

It has been pointed out that facilitation is effective in fostering collaboration in conflict management particularly in conflicts which are complex in nature or those that involve multiple parties. In such conflicts, it is necessary to seek outside help from a neutral third party to facilitate the discussion as parties work towards mutually acceptable outcomes.

Applying collaborative approaches towards conflict management offers several advantages. It has been pointed out that collaborating results in mutually acceptable solutions. Such solutions can therefore be effective and long lasting negating the likelihood of conflicts reemerging in future. Collaborating signifies joint efforts, gain for both parties and integrated solutions arrived at by consensual decisions.

Collaborating is also very effective when it is necessary to build or maintain relationships since it focuses on the needs and interests of all parties in a dispute. It has been observed that collaborative approaches emphasize trust-building, open communication, and empathizing with each other’s perspectives which goes beyond resolving conflicts to facilitate deeper understandings of each other. Collaborative approaches can therefore lead to better interpersonal connections.

Collaborating can also result in constructive decision-making since encouraging active engagement and open dialogue helps others think outside of the box and explore innovative paths towards conflict management. Further, by encouraging the participation and involvement of all stakeholders, collaboration ensures that everyone feels heard, valued and understood which is very essential in managing conflicts.

In addition, collaborating sets the tone for future conflict resolutions since it gives those involved the shared responsibility to resolve their problems. However, collaborative approaches towards conflict management have also been associated with several drawbacks. For example, it has been observed that collaborative approaches may not be easy to implement since they involve a lot of effort to get an actionable solution. It has been observed that thorough discussions, active participation, and exploring multiple perspectives as envisaged by collaborative approaches take time.

Collaborating may therefore require patience and dedication to ensure all voices are heard and meaningful resolutions are reached. Achieving consensus through collaborative approaches can also be difficult since conflicting opinions, varying conflict goals, and emotional variables can make the consensus-building process challenging and time-consuming. As a result of these challenges, it has been asserted that collaborative approaches towards conflict management are frequently the most difficult and time-consuming to achieve.

Further, it has been argued that over use of collaboration and consensual decision-making may reflect risk aversion tendencies or an inclination to defuse responsibility. Despite these challenges, collaborative approaches towards conflict management are ideal in ensuring win-win and long lasting outcomes. It is therefore necessary to embrace and apply collaborative approaches towards conflict management.

*This is an extract from Kenya’s First Clean and Healthy Environment Book: Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya and Academic Champion of ADR 2024. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2024 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Bercovitch. J., ‘Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations: A Framework for Analysis.’ Available at https://ocd.lcwu.edu.pk/cfiles/International%20Relations/EC/IR403/Conflict.ConflictManagementinOrga nizations.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Bercovitch. J., ‘Mediation Success or Failure: A Search for the Elusive Criteria.’ Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 7, p 289.

Bloomfield. D., ‘Towards Complementarity in Conflict Management: Resolution and Settlement in Northern Ireland,’ Journal of Peace Research., Volume 32, Issue 2.

Burrell. B., ‘The Five Conflict Styles’ Available at https://web.mit.edu/collaboration/mainsite/ modules/module1/1.11.5.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Demmers. J., ‘Theories of Violent Conflict: An Introduction’ (Routledge, New York, 2012).

Diana. M., ‘From Conflict to Collaboration’ Available at https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/conflict-collaboration-beyond-projectsuccess-1899 (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization., ‘Collaborative Conflict Management for Enhanced National Forest Programmes (NFPs)’ Available at https://www.fao.org/3/i2604e/i2604e00.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

International Organization for Peace Building., ‘Natural Resources and Conflict: A Path to Mediation.’ Available at https://www.interpeace.org/2015/11/naturalresources-and-conflict-a-path-to-mediation/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Isenhart. M.W., & Spangle. M., ‘Summary of “Collaborative Approaches to Resolving Conflict” ‘ Available at https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/isenhart-collaborative (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Kaushal. R., & Kwantes. C., ‘The Role of Culture and Personality in Choice of Conflict Management Strategy.’ International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (2006) 579– 603.

Leeds. C.A., ‘Managing Conflicts across Cultures: Challenges to Practitioners.’ International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 2, No. 2, 1997.

May. E., ‘Collaborating Conflict Style Explained In 4 Minutes’ Available at https://www.niagara institute.com/blog/collaborating-conflict-style/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Miroslavov. M., ‘Mastering the Collaborating Conflict Style In 2024’ Available at https://www.officernd.com/blog/collaborating-conflictstyle/#:~:text=It’s%20one%20of%20the%20strat egies,their%20underlying%20needs %20and%20interests. (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K & Kariuki. F., ‘ADR, Access to Justice and Development in Kenya.’ Available at http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ADR-access-tojustice-and-development-inKenyaRevised-version-of-20.10.14.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution and Access to Justice in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2015.

Muigua. K., ‘Reframing Conflict Management in the East African Community: Moving from Alternative to ‘Appropriate’ Dispute Resolution.’ Available at https://kmco.co.ke/wpcontent/uploads/2023/06/ Reframing-ConflictManagement-in-the-East-African-CommunityMoving-from-Alternative-toAppropriate-Dispute-Resolution (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Resolving Conflicts through Mediation in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2nd Edition., 2017.

Quain. S., ‘The Advantages & Disadvantages of Collaborating Conflict Management’ Available at https://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantagesdisadvantages-collaborating-conflict-management-36052.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Samuel. A., ‘Is the Collaborative Style of Conflict Management the Best Approach?’ Available at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/collaborative-style-conflictmanagement-best-approach-samuel-ansah (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

United Nations., ‘Land and Conflict’ Available at https://www.un.org/en/landnatural-resources-conflict/pdfs/GN_ExeS_Land%20and%20Conflict.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Weiss. J., & Hughes. J., ‘Want Collaboration?: Accept—and Actively Manage— Conflict’ Available at https://hbr.org/2005/03/want-collaboration-accept-andactively-manage-conflict (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

News & Analysis

Collaborative Approaches towards Conflict Management

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 23, 2024By

Admin

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is the Academic Champion of ADR 2024, the African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, the African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) and Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, March 2024)*

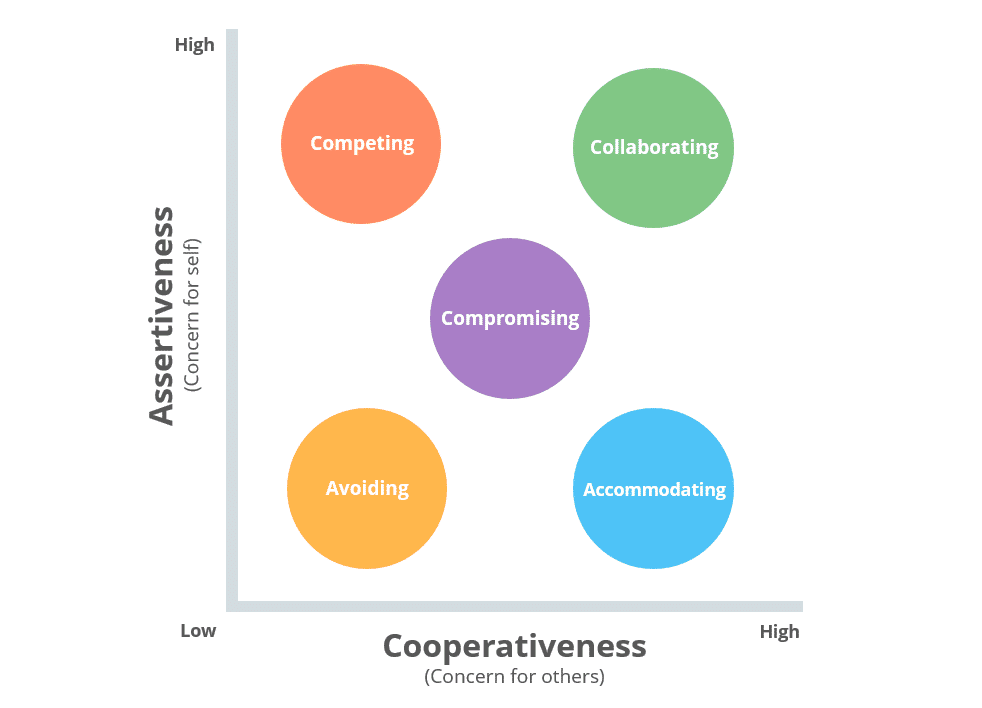

Conflict management can involve different approaches. These techniques include collaborating, competing, avoiding, accommodating, and compromising. Collaborative approaches towards conflict management have been hailed as the most ideal due to their potential to produce satisfactory and long-term results. Collaborative approaches have been hailed as ensuring efficient and effective management of conflicts towards peace and sustainability.

Collaborative conflict management refers to the use of a wide range of informal approaches where competing or opposing stakeholder groups work together to reach an agreement on a controversial issue. In addition, it has been pointed out that collaborative conflict resolution encourages teams to work through disagreements through empathy, listening, and mutually beneficial solutions. Collaboration, unlike compromise, does not focus on both sides making sacrifices. Instead, in collaborative approaches, both parties come up with mutually beneficial solutions. Collaborating has been identified as a powerful approach to conflict resolution built on cooperation, open communication, and finding win-win outcomes.

It has been argued that among all conflict management techniques, collaborative approaches are the most likely to identify the root cause of a conflict, pinpoint the underlying needs of the parties involved, and come to a win-win outcome for everyone. Through collaboration, all parties to a conflict come together to openly discuss the issue causing tension, actively listen to each other, and work towards a solution that is mutually satisfactory and acceptable to everyone.

It has been pointed out that collaborative conflict management aims to achieve several objectives which include: promoting the participation of diverse or competing stakeholder groups in order to reach agreement on a controversial issue; assisting stakeholders in adopting an attitude that is oriented towards cooperation rather than pursuit of individual interests; establishing new forms of communication and decision making on important issues, and raising awareness of the importance of equity and accountability in stakeholder communication; developing partnerships and strengthening stakeholder networks; creating space for stakeholders to communicate in order to bring about future agreements so that concrete action can be taken; and producing decisions that have a strong base of support.

In addition, it has been observed that collaborative approaches towards conflict management aim to preserve relationships, build trust, and promote long term positive change. Collaborative conflict management is based on certain principles key among them being ensuring open communication, finding common ground, and creating a culture of trust. Collaborative approaches towards conflict management has been hailed as the “win-win” strategy to conflict management. It is an effective means of restoring peace.

Further, it has been argued that collaborative approaches are a better way to conflict management since they encourage freedom of expression, where the conflicting parties express their thoughts and concerns verbally, which makes all parties involved in the dispute feel valued and be aware of each other’s concern. In addition, it has been argued that collaborating sets the tone for future conflict resolution and gives those involved the shared responsibility to manage conflicts prior to escalation.

Managing conflicts in a collaborative way helps to develop trust and strengthen communication channels between the various parties. For example, it has been pointed out that in conflicts related to natural resources, collaborative approaches help in generating inclusive solutions that arise from wider stakeholders’ views, and therefore helps clarify policies, institutions and processes that regulate access to – or control over – natural resources. It has been observed that collaborating entails all parties to a conflict sitting down together, discussing the conflict, and working towards a solution together.

Collaborative approaches towards conflict management have been identified as vital when it is necessary to maintain all parties’ relationships or when the solution itself will have a significant impact on large group of people. In such situations, collaborating ensures a win-win solution is found so that everyone is satisfied which creates the condition for peace and sustainability.

It has been pointed out that for collaborative approaches to be effective, it is necessary for all parties to have collaborating skills such as the ability to use active or effective listening, confront situations in a nonthreatening way, analyze input, and identify underlying concerns. Collaborative approaches towards conflict management are important in fostering effective and long-lasting outcomes. It is therefore necessary to apply collaborative approaches in order to ensure effective and efficient management of conflicts.

*This is an extract from Kenya’s First Clean and Healthy Environment Book: Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya and Academic Champion of ADR 2024. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2024 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Bercovitch. J., ‘Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations: A Framework for Analysis.’ Available at https://ocd.lcwu.edu.pk/cfiles/International%20Relations/EC/IR403/Conflict.ConflictManagementinOrga nizations.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Bercovitch. J., ‘Mediation Success or Failure: A Search for the Elusive Criteria.’ Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 7, p 289.

Bloomfield. D., ‘Towards Complementarity in Conflict Management: Resolution and Settlement in Northern Ireland,’ Journal of Peace Research., Volume 32, Issue 2.

Burrell. B., ‘The Five Conflict Styles’ Available at https://web.mit.edu/collaboration/mainsite/ modules/module1/1.11.5.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Demmers. J., ‘Theories of Violent Conflict: An Introduction’ (Routledge, New York, 2012).

Diana. M., ‘From Conflict to Collaboration’ Available at https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/conflict-collaboration-beyond-projectsuccess-1899 (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization., ‘Collaborative Conflict Management for Enhanced National Forest Programmes (NFPs)’ Available at https://www.fao.org/3/i2604e/i2604e00.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

International Organization for Peace Building., ‘Natural Resources and Conflict: A Path to Mediation.’ Available at https://www.interpeace.org/2015/11/naturalresources-and-conflict-a-path-to-mediation/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Isenhart. M.W., & Spangle. M., ‘Summary of “Collaborative Approaches to Resolving Conflict” ‘ Available at https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/isenhart-collaborative (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Kaushal. R., & Kwantes. C., ‘The Role of Culture and Personality in Choice of Conflict Management Strategy.’ International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (2006) 579– 603.

Leeds. C.A., ‘Managing Conflicts across Cultures: Challenges to Practitioners.’ International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 2, No. 2, 1997.

May. E., ‘Collaborating Conflict Style Explained In 4 Minutes’ Available at https://www.niagara institute.com/blog/collaborating-conflict-style/ (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Miroslavov. M., ‘Mastering the Collaborating Conflict Style In 2024’ Available at https://www.officernd.com/blog/collaborating-conflictstyle/#:~:text=It’s%20one%20of%20the%20strat egies,their%20underlying%20needs %20and%20interests. (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K & Kariuki. F., ‘ADR, Access to Justice and Development in Kenya.’ Available at http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ADR-access-tojustice-and-development-inKenyaRevised-version-of-20.10.14.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution and Access to Justice in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2015.

Muigua. K., ‘Reframing Conflict Management in the East African Community: Moving from Alternative to ‘Appropriate’ Dispute Resolution.’ Available at https://kmco.co.ke/wpcontent/uploads/2023/06/ Reframing-ConflictManagement-in-the-East-African-CommunityMoving-from-Alternative-toAppropriate-Dispute-Resolution (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Muigua. K., ‘Resolving Conflicts through Mediation in Kenya.’ Glenwood Publishers Limited, 2nd Edition., 2017.

Quain. S., ‘The Advantages & Disadvantages of Collaborating Conflict Management’ Available at https://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantagesdisadvantages-collaborating-conflict-management-36052.html (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Samuel. A., ‘Is the Collaborative Style of Conflict Management the Best Approach?’ Available at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/collaborative-style-conflictmanagement-best-approach-samuel-ansah (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

United Nations., ‘Land and Conflict’ Available at https://www.un.org/en/landnatural-resources-conflict/pdfs/GN_ExeS_Land%20and%20Conflict.pdf (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Weiss. J., & Hughes. J., ‘Want Collaboration?: Accept—and Actively Manage— Conflict’ Available at https://hbr.org/2005/03/want-collaboration-accept-andactively-manage-conflict (Accessed on 01/03/2024).

Irene Kiwool: My Track Record and Call to PACT for Better Nairobi LSK

A Toolkit for Customers on accessing Financial Services in Kenya

Way Forward in Applying Collaborative Approaches Towards Conflict Management

Opportunities and Challenges of Collaborative Conflict Management

Collaborative Approaches towards Conflict Management

Way Forward in Fostering the Blue Economy for Sustainability

Trending

-

Lawyers11 months ago

Lawyers11 months agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame | Kenya in 2023

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoThe Definition and Scope of Biodiversity

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoThe Definition, Aspects and Theories of Development

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

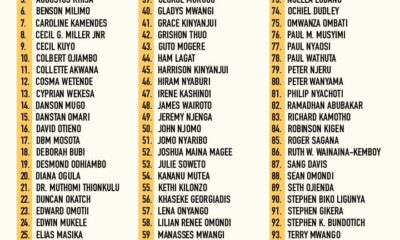

News & Analysis2 years agoTHE TOP 200 ARBITRATORS IN KENYA 2022

-

News & Analysis6 months ago

News & Analysis6 months agoThe Role of NEMA in Pollution Control in Kenya

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoRole of Science and Technology in Environmental Management in Kenya

-

Lawyers11 months ago

Lawyers11 months agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Top 100 Litigation Lawyers in Kenya 2023

-

News & Analysis7 months ago

News & Analysis7 months agoHow to Become an Arbitrator in Kenya