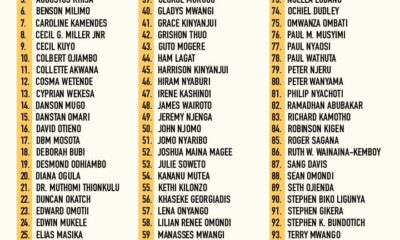

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is the Academic Champion of ADR 2024, the African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, the African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023) and Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024)*

It has been posited that the basic principles for effective water governance include open and transparent, inclusive and communicative, coherent and integrative, equitable and ethical approaches while in terms of performance, the basic attributes include accountable, efficient, responsive and sustainable operations. The degree of integration of the principles and attributes in any system serve as good indicators of whether the system will be able to achieve effective governance or not. Taking a human right approach to water and encouraging public participation in water governance can go a long way in bridging the gap towards effective governance of water resources for realization of sustainable development agenda.

A Human Rights Approach to Water

It has been acknowledged that one of the problems believed to contribute to inequitable access to water is a perception among community members that there are cartels comprising of powerful politicians, employees of water service providers, water vendors, and government employees, among others who are out to ensure that the status quo of the existing water problems is maintained. It is estimated that over 50% of Kenya’s households do not have access to safe drinking water and the proportion is higher for the poor.

It is noteworthy that the user water rights are different from the human right to water in that while water rights are the legal authorization to use a specified quantity of water “for a specific purpose under specific conditions,” the human right to water focuses on the amount and quality of water required by human beings to meet their basic needs, which should serve as a minimum requirement for water rights to be granted to each individual. From the Act, it seems that the law places greater emphasis on the water rights while sidelining the human right to water. This is seen from the emphasis on licenses for the various uses of water. There are inadequate provisions placing elaborate responsibility on the various institutions and governance bodies in implementation of the human right to water.

The UN General Assembly Resolution on the human right to water and sanitation formally recognises the right to water and sanitation and acknowledges that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realisation of all human rights. The Resolution calls upon States and international organisations to provide financial resources, help capacity-building and technology transfer to help countries, in particular developing countries, to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all. The implementation of the Act should adopt a human rights approach which would help in addressing the inequitable distribution and access to water resources.

Public Participation in Water Governance

Public participation means different things to different people and may take several forms, ranging from information supply— to consultation, discussions with the public, co-decision making—to a situation in which the “public” is in charge of parts of natural resources management, for example, through water users’ associations. Public participation would improve the quality of decision making by opening up the decision-making process and making better use of the information and creativity that is available in society. Moreover, it would improve public understanding of the management issues at stake, make decision making more transparent, and might stimulate the different government bodies involved to coordinate their actions more in order to provide serious follow-up to the inputs received.

Management itself would become less controversial, less litigation would take place, and implementation of decisions would be much smoother. Finally, public participation could improve democracy. Public participation would be imperative whenever government does not have enough resources (information, finance, power, etc.) to manage an issue effectively, as is usually the case in water management. Scholars have argued that inclusiveness requires wide participation throughout the policy chain right from conception to implementation. Furthermore, participation is necessary to make decisions more politically acceptable and to foster accountability and stakeholders should collectively design and implement policies and management strategies that meet their goals effectively and acceptably.

It has been argued that the community-based water governance systems anchored in unwritten customary norms and values shape perceptions of water rights and water governance at local levels. The Community-based norms and practices often referred to as ‘living customary law,’ have endured in spite of efforts by both colonial and independent African governments to redefine citizen’s relationship to water through state laws and policies.

This is an extract from Kenya’s First ESG Law Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya and Academic Champion of ADR 2024. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2024 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Akech, J.M.M., ‘Governing Water and Sanitation in Kenya: Public Law, Private Sector Participation and The Elusive Quest for A Suitable Institutional Framework,’ Paper prepared for the workshop entitled ‘Legal Aspects of Water Sector Reforms’ to be organised in Geneva from 20 to 21 April 2007 by the International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC) in the context of the Research partnership 2006-2009 on water law sponsored by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), p. 6. Available at http://www.ielrc.org/activities/workshop_0704/content/d0702.pdf [Accessed on 5/01/2017].

Budds, J. & McGranahan, G., ‘Are the debates on water privatization missing the point? Experiences from Africa, Asia and Latin America,’ Environment & Urbanization, Vol. 15, No. 2, October 2003, pp. 87-114 at p. 87.

Concern Worldwide Kenya, ‘Five year ASAL Water Hygiene and Sanitation Strategy for Marsabit County 2013 – 2018,’ (Dublin Institute of Technology), p.4.

Constitution of Kenya 2010 (Government Printer, 2010, Nairobi).

Gorre-Dale, E., ‘The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development’, Environmental Conservation, Vol. 19, No.2, 1992, p. 181. Available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridgecore/content/view/843EB9B98E0F63A3DA36041F7BF3BF16/S0376892900030733a.pdf/div -class-title-the-dublin-statement-on-water-and-sustainable-development-div.pdf [Accessed on 05/10/2016].

Hellum, A., et al, ‘The Human Right to Water and Sanitation in a Legal Pluralist Landscape: Perspectives of Southern and Eastern African Women,’ in Hellum A., et al (eds), Water is Life: Women’s Human Rights in National and Local Water Governance in Southern and Eastern Africa, (Weaver Press, Harare, 2015), p. 10.

Huitema, D., et al, ‘Adaptive Water Governance: Assessing the Institutional Prescriptions of Adaptive (Co-)Management from a Governance Perspective and Defining a Research Agenda,’ Ecology and Society, Vol. 14, No.1, pp.1-26 at p. 5.

K’Akumu, O.A., ‘Toward effective governance of water services in Kenya,’ Water Policy, Vol. 9, 2007, pp.529–543 at p. 530.

Mirosa, O. & Harris, L.M., ‘Human Right to Water: Contemporary Challenges and Contours of a Global Debate,’ Antipode, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2012, pp. 932-949 at p. 935.

Moraa, H., Water governance in Kenya: Ensuring Accessibility, Service delivery and Citizen Participation, (iHub Research, July 2012), p.9. Available at http://ihub.co.ke/ihubresearch/uploads/2012/july/1343052795__537.pdf.

Nkonya, L.K., ‘Realizing the Human Right to Water in Tanzania,’ op cit. p. 25. 10 United Nations, General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water (Arts. 11 and 12 of the Covenant), Adopted at the Twenty-ninth Session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, on 20 January 2003 (Contained in Document E/C.12/2002/11).

Nkonya, L.K., ‘Realizing the Human Right to Water in Tanzania,’ op cit. p. 26. 85 The United Nations General Assembly Resolution, the human right to water and sanitation, A/RES/64/292, July 2010.

Perry, C.J., et al, Water as an Economic Good: A Solution, or a Problem? Research Report 14, (International Irrigation Management Institute, Colombo, 1997), p. 1. 49.

Tortajada, C., ‘Water Governance: Some Critical Issues,’ International Journal of Water Resources Development, Vol. 26, No.2, 2010, pp.297-307, p. 298.

Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water (Arts. 11 and 12 of the Covenant), 20 January 2003, E/C.12/2002/11. Adopted at the Twenty-ninth Session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, on 20 January 2003 (Contained in Document E/C.12/2002/11).

UN Water, ‘Climate Change Adaptation: The Pivotal Role of Water,’ available at http://www.unwater.org/downloads/unw_ccpol_web.pdf [Accessed on 05/2/2016].

United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, ‘Commercialization, Privatization and Universal Access to Water,’ available at http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BB128/(httpProjects)/E8A27BFBD688C0A0C1 256E6D0049D1BA [ Accessed on 5/1/2017].

United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, ‘Commercialization, Privatization and Universal Access to Water,’ available at http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BB128/(httpProjects)/E8A27BFBD688C0A0C1256E 6D0049D1BA.

United Nations, ‘International Decade for Action ‘water for Life 2005-2015’: Water and sustainable development,’ available at http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/water_and_sustainable_development.shtml [Accessed on 05/10/2016].

United Nations, The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development, Adopted January 31, 1992 in Dublin, Ireland, International Conference on Water and the Environment. Dublin, Ireland, International Conference on Water and the Environment, available at http://un-documents.net/h2o-dub.htm [Accessed on 05/10/2016].

Water Act 2016, Laws of Kenya (Government Printer, 2010, Nairobi).

Lawyers2 years ago

Lawyers2 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

Lawyers2 years ago

Lawyers2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago