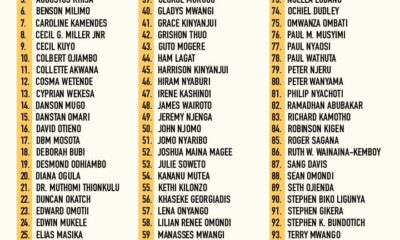

By Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD (Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Policy Advisor, Natural Resources Lawyer and Dispute Resolution Expert from Kenya), Winner of Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021, ADR Publication of the Year 2021 and CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021*

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 recognizes culture as the foundation of the nation and as the cumulative civilization of the Kenyan people and nation. In light of this, it obligates the State to, inter alia, promote all forms of national and cultural expression through literature, the arts, traditional celebrations, science, communication, information, mass media, publications, libraries and other cultural heritage; and recognize the role of science and indigenous technologies in the development of the nation. The Constitution provides that the State shall protect and enhance indigenous knowledge of biodiversity of the communities. The State is also obliged to encourage public participation in the management, protection and conservation of the environment. In doing so, the State is also obligated to supply the relevant environmental information.

Article 35(1) of the Constitution states that every citizen has the right of access to—(a) information held by the State; and (b) information held by another person and required for the exercise or protection of any right or fundamental freedom. Access to Information Act, 2015, which is intended to give effect to Article 35 of the Constitution; to confer on the Commission on Administrative Justice the oversight and enforcement functions and powers and for connected purposes. It classifies environmental information as part of the information that falls under information affecting public interest. Such environmental information is necessary to enable communities make informed decisions. Thus decision-making processes should focus on the supply of the right information, incentives, resources and skills to citizens so that they can increase their resilience and adapt to climate change and other environmental changes.

Notably, sustainable development involves adoption of sustainable methods of managing conflicts and disputes. In settling land disputes, communities are encouraged to apply recognized local community initiatives consistent with the Constitution. This will enhance community involvement in natural resource management thus enhancing their participation in achieving peace for sustainable livelihoods. All these provisions encourage in one way or the other the participation of local communities in the management, use or ownership of natural resources and most importantly, using their indigenous knowledge as a knowledge reference point.

The Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions Act, 2016, which seeks to provide a unified and comprehensive framework for the protection and promotion of traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions; and to give effect to Articles 11, 40(5) and 69 of the Constitution, recognises the intrinsic value of traditional cultures and traditional cultural expressions, including their social, cultural, economic, intellectual, commercial and educational value. While the Act does not expressly mention the words ‘sustainable development’, it provides that equitable benefit sharing rights of the owners and holders of traditional knowledge or cultural expressions shall include the right to fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the commercial or industrial use of their knowledge, which right might extend to non-monetary benefits, such as contributions to community development, depending on the material needs and cultural preferences expressed by the communities themselves.

Notably, 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under Goal 16 which seeks to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels, calls for states to ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels. The SDGs also pledge to foster intercultural understanding, tolerance, mutual respect and an ethic of global citizenship and shared responsibility. They also acknowledge the natural and cultural diversity of the world and recognise that all cultures and civilizations can contribute to and are enablers of, sustainable development. The provisions in the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions Act, 2016 thus offer a rare opportunity for the state to realize the vision of the 2030 SDGs by incorporating Kenyan communities’ indigenous knowledge in the roadmap to the achievement of the sustainable development agenda. By including these communities and their knowledge, any development policies aimed to benefit these communities will be more likely to not only respond to their cultural needs and preferences but will also enable them meaningfully participate.

The Environmental Management and Conservation Act (EMCA) is the overarching law on environmental matters in Kenya. It is a framework environmental law establishing legal and institutional mechanisms for the management of the environment. It provides for improved legal and administrative co-ordination of the diverse sectoral initiatives in order to improve the national capacity for the management of the environment. Section 44 of the Act, mandates the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), in consultation with the relevant lead agencies, to develop, issue and implement regulations, procedures, guidelines and measures for the sustainable use of hill sides, hill tops, mountain areas and forests. It also requires the formulation of regulations, guidelines, procedures and measures aimed at controlling the harvesting of forests and any natural resources located in or on a hill side, hill top or mountain areas so as to protect water catchment areas, prevent soil erosion and regulate human settlement.

Section 46(1) requires every County Environment Committee to specify the areas identified in accordance with section 45(1) as targets for afforestation or reforestation. A County Environment Committee is to take measures, through encouraging voluntary self-help activities in their respective local community, to plant trees or other vegetation in any areas specified under subsection (1) which are within the limits of its jurisdiction. It is noteworthy that such afforestation may be ordered to be carried out even in private land. Paragraph (3) thereof is to the effect that where the areas specified under subsection (1) are subject to leasehold or any other interest in land, including customary tenure, the holder of that interest shall implement measures required to be implemented by the District Environment Committee, including measures to plant trees and other vegetation in those areas.

Under section 48, the Director-General with the approval of the Director of Forestry, may enter into any contractual arrangement with a private owner of any land on such terms and conditions as may be mutually agreed for the purposes of registering such land as forest land. The powers of the Authority include the issuance of guidelines and prescribing measures for the sustainable use of hill tops, hill slides and mountainous areas. To promote environmental justice and community participation in environmental matters, section 48 (2) prohibits the Director-General from taking any action, in respect of any forest or mountain area, which is prejudicial to the traditional interests of the indigenous communities customarily resident within or around such forest or mountain area.

The general objectives of the Environmental Management and Co-ordination (Wetlands, River Banks, Lake Shores and Sea Shore Management) Regulation, 2009 (dealing with wetlands management) include, inter alia: to provide for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands and their resources in Kenya; to promote the integration of sustainable use of resources in wetlands into the local and national management of natural resources for socio-economic development; to ensure the conservation of water catchments and the control of floods; to ensure the sustainable use of wetlands for ecological and aesthetic purposes for the common good of all citizens; to ensure the protection of wetlands as habitats for species of fauna and flora; provide a framework for public participation in the management of wetlands; to enhance education research and related activities; and to prevent and control pollution and siltation.

Regulation 5(1) thereof provides for the general principles that shall be observed in the management of all wetlands in Kenya including: Wetland resources to be utilized in a sustainable manner compatible with the continued presence of wetlands and their hydrological, ecological, social and economic functions and services; Environmental impact assessment and environmental audits as required under the Act to be mandatory for all activities likely to have an adverse impact on the wetland; Special measures to promote respect for, preserve and maintain knowledge innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and promote their wider application with the approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of such knowledge, innovations and practices; Sustainable use of wetlands to be integrated into the national and local land use plans to ensure sustainable use and management of the resources; principle of public participation in the management of wetlands; principle of international co-operation in the management of environmental resources shared by two or more states; the polluter-pays principle; the pre-cautionary principle; and public and private good. These are some of the initiatives that highlight the existing relationship between community indigenous and cultural knowledge and sustainable development, thus affirming the fact that cultural issues cannot be wished away in the discussion and efforts towards achieving sustainable development in Kenya and the world over.

*This is article is an extract from an article by Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya): Muigua, K., Revisiting the Place of Indigenous Knowledge in the Sustainable Development Agenda, Available at: http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Revisiting-the-Place-of-Indigenous-Knowledge-in-the-Sustainable-Development-Agenda-Kariuki-Muigua-September-2020.pdf. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is Kenya’s foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a Senior Lecturer of Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law and The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP). He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Dr. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Africa Trustee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates. Dr. Muigua is recognized as one of the leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts by the Chambers Global Guide 2021.

References

Africa Forest Law Enforcement and Governance (AFLEG), Ministerial Conference 13-16 October, 2003; Ministerial Declaration, Yaoundé, Cameroon, October 16, 2003.

Amnesty Kenya, ‘Kenya: Indigenous Peoples Targeted as Forced Evictions Continue despite Government Promises’ https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/08/kenya-indigenous-peoples-targeted-as-forced-evictions-continue-despite-government-promises/ (accessed 16 July 2020).

Berger, R., ‘Conflict over Natural Resources among Pastoralists in Northern Kenya: A Look at Recent Initiatives in Conflict Resolution’ (2003) 15 Journal of International Development 245.

Berkes, F., et. al., ‘Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management,’ Ecological Applications, Vol. 10, No. 5., October 2000, pp. 1251-1262.

Breidlid, A., ‘Culture, Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Sustainable Development: A Critical View of Education in an African Context’ (2009) 29 International Journal of Educational Development 140.

Castro, A.P. & Ettenger, K., ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Conflict Management: Exploring Local Perspectives and Mechanisms For Dealing With Community Forestry Disputes,’ Paper Prepared for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Community Forestry Unit, for the Global Electronic Conference on “Addressing Natural Resource Conflicts Through Community Forestry,” (FAO, January-April 1996). Available at http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/ac696e/ac696e09.htm [Accessed on 14/7/2020].

Constitution of Kenya, Laws of Kenya, Government Printer, 2010.

Dessein, J. et al (ed), ‘Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development: Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability,’ (University of Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015), p. 14. Available at http://www.culturalsustainability.eu/conclusions.pdf [Accessed on 17/7/2020].

Emerton, L., ‘Mount Kenya: The Economics of Community Conservation,’ Evaluating Eden Series, Discussion Paper No.4, p. 6.

Environmental Management and Conservation Act (EMCA), No. 8 of 1999, Laws of Kenya.

Environmental Management and Co-ordination (Wetlands, River Banks, Lake Shores and Sea Shore Management) Regulation, 2009, Legal Notice No. 19, Act No. 8 of 1999.

Forest Conservation and Management Act, No. 34 of 2016, Laws of Kenya.

Giorgia Magni, ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Implications for the Sustainable Development Agenda.’ (2017) 52 European Journal of Education 437, p.3, Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/ pf0000245623> Accessed 17 July 2020.

Human Rights Watch, “They Just Want to Silence Us” (17 December 2018) https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/17/they-just-want-silence-us/abuses-against-environmental-activists-kenyas-coast (Accessed 17 July 2020).

Isaka Wainaina and Anor v Murito wa Indagara and others, [1922-23] 9 E.A.L.R. 102.

FAO, ‘FAO Working Paper 1’ https://www.fao.org/3/X2102E/X2102E01.htm (accessed 17 July 2020).

Kigenyi, et al, ‘Practice Before Policy: An Analysis of Policy and Institutional Changes Enabling Community Involvement in Forest Management in Eastern and Southern Africa,’ Issue 10 of Forest and social perspectives in conservation, (IUCN, 2002), p. 9.

Klopp, J.M. and Sang, J.K., ‘Maps, Power, and the Destruction of the Mau Forest in Kenya’ (2011) 12 Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 125;

Kriegler and Waki Reports on 2007 Elections, 2009, (Government Printer, Nairobi).

Mogaka, H., ‘Economic Aspects of Community Involvement in Sustainable Forest Management in Eastern and Southern Africa,’ Issue 8 of Forest and social perspectives in conservation, IUCN, 2001. p.74.

Muigua, K., ‘Mainstreaming Traditional EcologicalKnowledge in Kenya for Sustainable Development’, 2020 Journal of cmsd Volume 4(1)< http://journalofcmsd.net/wpcontent/uploads/ 2020/03/Mainstreaming-Traditional-Ecological-Knowledge-in-Kenya-for-SustainableDevelop ment-Kariuki-Muigua-23rd-August-2019.pdf> Accessed on 17 July 2020.

Muigua, K., Harnessing Traditional Knowledge for Environmental Conflict Management in Kenya (2016)< http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/TRADITIONAL-KNOWLEDGE -ANDCONFLICT-MANAGEMENT-29-SEPTEMBER-2016.pdf> accessed 17 July 2020.

Ogendo, HWO, Tenants of the Crown: Evolution of Agrarian Law & Institutions in Kenya, (ACTS Press, Nairobi, 1991), p.54.

Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions Act, 2016 No. 33 of 2016, Laws of Kenya.

Relief Web, ‘Families Torn Apart: Forced Eviction of Indigenous People in Embobut Forest, Kenya – Kenya’ (ReliefWeb) https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/families-torn-apart-forced-eviction-indigenous-people-embobut-forest-kenya-0 (accessed 16 July 2020).

Report of the Judicial Commission Appointed to Inquire into Tribal Clashes in Kenya, July 31, 1999 (Akiwumi Report, p. 59).

Swiderska, K., et. al., ‘Protecting Community Rights over Traditional Knowledge: Implications of Customary Laws and Practices,’ Interim Report (2005-2006), November 2006, p. 13. Available at http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/G01253.pdf [Accessed on 14/7/2020].

SGJN Senanayake, ‘Indigenous Knowledge as a Key to Sustainable Development’ (2006) 2 Journal of Agricultural Sciences–Sri Lanka accessed 16 July 2020. 5 Ibid. 6 United Nations General Assembly, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Resolution adopted by the

Urmilla, B., and Salomé Bronkhorst, ‘Environmental Conflicts: Key Issues and Management Implications’ (2010) 10 African Journal on Conflict Resolution.

UNFF Memorandum, available at www.iucnael.org/en/…/doc…/849-unit-3-forest-gamebackgrounder.html. > accessed 16 July 2020.

UNEP, Global Environment Outlook 5: Environment for the future we want, (UNEP, 2012), pp.145-154.

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago