Uncategorized

The Law and Practice on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Kenya

Published

3 years agoon

By

Admin

By Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD (Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Policy Advisor, Natural Resources Lawyer and Dispute Resolution Expert from Kenya), Winner of Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021, ADR Publication of the Year 2021 and CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021*

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a tool that helps those involved in decision-making concerning development programs or projects to make their decisions based on the knowledge of the likely impacts that will be caused to the environment.[1] EIA is an important tool for public participation in natural resources management. Internationally, the Convention on Biological Diversity in Article 14 requires public participation in EIA procedures. The need for EIA was also captured in Principle 17 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development in the following terms: Environmental impact assessment, as a national instrument, shall be undertaken for proposed activities that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment and are subject to a decision of a competent authority.[2]

In Kenya, EIA gets its legislative backing from section 42 of the Environmental Management and Coordination Act, Act No. 8 of 1999.[3] The procedure for EIA provided for under EMCA is designed to be quite comprehensive and to ensure public participation. The Act in section 58 requires proponent of any project specified in the Second Schedule[4] to undertake a full environmental impact assessment study and submit an environmental impact assessment study report to the Authority prior to being issued with any licence by the Authority: Provided that the Authority may direct that the proponent forego the submission of the environmental impact assessment study report in certain cases. The Act in section 59 then provides that the EIA study report shall be publicised for two successive weeks in the Kenya Gazette, a local newspaper and inviting members of the public to give their comments either orally or in writing on the proposed project within a period not exceeding sixty days.

Section 52 of the Act provides that the Authority may require any proponent of a project to carry out at his own expense further evaluation or environmental impact assessment study, review or submit additional information for the purposes of ensuring that the environmental impact assessment study, review or evaluation report is as accurate and exhaustive as possible. Thereafter, the Authority may, after being satisfied as to the adequacy of an environmental impact assessment study, evaluation or review report, issue an environmental impact assessment licence on such terms and conditions as may be appropriate and necessary to facilitate sustainable development and sound environmental management.[5]

In the Mui case,[6] the Court observed as follows:

- Having said that, we take cognizance of the fact that an Environmental Impact Assessment has not been completed. The Court therefore fully expects that the programme of public participation will continue even more robustly in the next phase of EIA. In particular, we expect that upon completion of the EIA the Government will follow the stipulations as directed under Regulation 17 of Legal Notice No. 101, the Environmental (Impact Assessment & Audit) Regulations 2003, and in disseminating the information to ensure that the relevant information is given to the public; these reports should be in a simple language that everyone can understand; the venues of the Barazas should be centrally convenient; the dates of the meetings should be known to all well in advance and the County Government should be involved from now henceforth.

- EIA is an obviously important component to this entire process as it is vanguard of the principles of sustainable development. It is from this assessment that we are guided as to the potential or lack of adverse effects of the project on the environment and where the decision will be made as to whether the project should continue or not.

In Bogonko v NEMA,[7] the applicant sought an order to quash NEMA’s decision to stop his project of putting up a petrol station. NEMA contended that it issued the order to stop the construction because the applicant had failed to publish the EIA study report for two successive weeks and hence the public was not given sufficient notice to comment on the report. The court held that the purpose of advertisement as provided for by the law is to ensure that the public see the proposed project and give their comments as to whether the project is viable or not. In the present case, the members of the public were denied such an opportunity. The court, therefore, declined to quash the order stopping the project because according to it, the public interest far outweighed the applicant’s individual right to put up a petrol station.

Similarly, in Kwanza Estates Ltd. v KWS,[8] the plaintiff sought orders to have KWS restrained from constructing a public toilet at the beach front as the toilet when in use would cause adverse environmental effects and devalue the plaintiffs prime beach property. KWS did not conduct an EIA before putting up the toilet. The court held that public participation was what informed the requirement for an EIA being done before any project commenced. The requirement for publicizing the report is what gave members of the public, like the plaintiff in this case, a voice in issues that may bear negatively on their right to a clean and healthy environment. The court proceeded to grant an injunction restraining KWS from constructing the toilet in the absence of an EIA to show how the waste from the toilet would be treated to prevent pollution in the ocean. EIA is a continuous process that goes on throughout the duration of the project.[9]

In addition to EIA, section 57A of EMCA provides for Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) which should be undertaken much earlier in the decision-making process than project environmental impact assessment (EIA). While the parent Act (EMCA) was initially silent on SEA, the same was introduced via the Environmental Management and Co-ordination (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Amendment Act 2015). The Amendment Act 2015 defines SEA under section 2 thereof to mean a formal and systematic process to analyze and address the environmental effects of policies, plans, programmes and other strategic initiatives. Whereas EIA concerns itself with the biophysical impacts of proposals only (e.g. effects on air, water, flora and fauna, noise levels, climate etc), SEA and integrated impact assessment analyze a range of impact types including social, health and economic aspects.[10] SEA is, arguably, not a substitute for EIA or other forms of environmental assessment, but a complementary process and one of the integral parts of a comprehensive environmental assessment tool box.[11]

*This article is an extract from the Article Fostering the Principles of Natural Resources Management in Kenya, 8(1) Journal of Conflict Management and Sustainable Development, p. 1 by Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya). Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a Senior Lecturer of Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law and The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP). He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Dr. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Africa Trustee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates. Dr. Muigua is recognized as one of the leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts by the Chambers Global Guide 2022.

References

[1] Angwenyi, A.N., ‘An Overview of the Environmental Management and Coordination Act,’ in Okidi, C.O., et al, (eds), Environmental Governance in Kenya: Implementing the Framework Law (East Africa Educational Publishers, 2008) p.167.

[2] 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26 (vol. I) / 31 ILM 874 (1992).

[3] Part VI – Integrated Environmental Impact Assessment (sec. 57A-67). See also Environmental (Impact Assessment and Audit) Regulations, 2003, Legal Notice No. 101 of 2003.

[4] Second Schedule [Section 58, Act No. 5 of 2015, s. 80.]- Projects Requiring Submission of an Environmental Impact Assessment Study Report.

[5] Section 63 of EMCA.

[6] 7 Mui Coal Basin Local Community & 15 others v Permanent Secretary Ministry of Energy & 17 others [2015] eKLR, Constitutional Petition Nos 305 of 2012, 34 of 2013 & 12 of 2014(Formerly Nairobi Constitutional Petition 43 of 2014) (Consolidated)

[7] [2006] 1KLR (E&L) 772.

[8] HCCC No. 133 of 2012, [2013] eKLR

[9] S. 64 of EMCA.

[10] Muigua, K., Legal Aspects of Strategic Environmental Assessment and Environmental Management, available at http://kmco.co.ke/wp[10]content/uploads/2018/08/Legal-Aspects-of-SEA-and-Environmental-Management[10]3RD-December-2016.pdf [Accessed on 21/02/2021].

[11] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, ‘Applying Strategic Environmental: Assessment Good Practice Guidance for Development Co[11]Operation,’ DAC Guidelines and Reference Series, 2006, p. 32. Available at http://www.oecd.org/environment/environment-development/37353858.pdf [Accessed on 21/02/2022].

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

You may like

-

The Challenges in Actualizing Sustainable Blue Economy in Kenya

-

The Meaning of Blue Economy in Kenyan Context

-

The Meaning of Environmental Pollution in Kenya

-

Overview of Human Right to Clean, Safe and Healthy Environment

-

What Issues are Required for ESG Reporting in Kenya?

-

Value Creation as an ESG Management Strategy

Uncategorized

Climate Finance Beyond COP 28: Introducing Loss and Damage Fund

Published

8 months agoon

February 14, 2024By

Admin

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is The African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, The African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023) and Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024)*

Climate finance refers to local, national, regional, continental and global financing of public and private investment that seeks to support mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. Climate finance has also been defined as finance for activities aimed at mitigating or adapting to the impacts of climate change. The United Nations defines climate finance as local, national or transnational financing drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change. Climate finance can therefore be understood as the flow of funds to all activities, programmes or projects intended to help address climate change through both mitigation and adaptation across the world.

Climate finance is very essential in enhancing the global response to climate change. Climate finance is needed for mitigation, because large-scale investments are required to significantly reduce emissions. Further, climate finance is equally important for adaptation, as significant financial resources are needed to adapt to the adverse effects and reduce the impacts of climate change. Climate finance is therefore necessary in combating climate change since the adaptation and mitigation processes vital in enhancing national, regional and global response to climate change require funding.

The concept of climate finance is premised on the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities’ which calls upon developed countries to provide financial resources to assist developing countries to respond to climate change. The principle of common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities has been embraced under the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC)9 and the Paris Agreement which urge developed countries to take the lead in mobilizing and unlocking climate finance.This principle recognizes that the contribution of countries to climate change and their capacity to prevent it and cope with its consequences vary enormously.

The Loss and Damage Fund was launched at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference/ Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP 27) when parties agreed to set up funding arrangements for responding to loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including a focus on addressing loss and damage. The objective of the Loss and Damage Fund is to establish new funding arrangements for assisting developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, in responding to loss and damage, including with a focus on addressing loss and damage by providing and assisting in mobilizing new and additional resources, and that these new arrangements complement and include sources, funds, processes and initiatives under and outside the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement.

The COP 27 decision also stipulates ways of operationalizing the Loss and Damage Fund including establishing institutional arrangements, modalities, structure, governance and terms of reference for the fund, defining the elements of the new funding arrangements, identifying and expanding sources of funding and ensuring coordination and complementarity with existing funding arrangements. It further establishes a Transitional Committee to operationalize the new funding arrangements for responding to loss and damage and the associated fund. The Committee made recommendations based on, inter alia, elements for operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund for consideration and adoption by the Conference of the Parties at COP 28.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund was the culmination of decades of pressure from climate-vulnerable developing countries. UNEP observes that the fund aims to provide financial assistance to nations most vulnerable and impacted by the effects of climate change. It has been asserted that the Loss and Damage Fund acknowledges that climate change has caused widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people beyond natural climate variability.

The United Nations points out that some development and adaptation efforts have reduced climate vulnerability, but the rise in weather and climate extremes has led to some irreversible impacts as natural and human systems are pushed beyond their ability to adapt. Loss and damage arising from the adverse impacts of climate change can include those related to extreme weather events but also slow onset events, such as sea level rise, increasing temperatures, ocean acidification, glacial retreat and related impacts, salinization, land and forest degradation, loss of biodiversity and desertification.

According to UNEP, loss and damage refers to the negative consequences that arise from the unavoidable risks of climate change, like rising sea levels, prolonged heatwaves, desertification, the acidification of the sea and extreme events, such as bushfires, species extinction and crop failures. The Loss and Damage Fund has been hailed as an important milestone in the climate justice agenda. The concept of climate justice acknowledges that climate change has had uneven and unequal burdens across the globe with nations and communities that contribute the least to climate change suffering the most from its consequences.

It has correctly been pointed out that some countries mainly the large industrialised economies of Europe and North America have benefitted much more from the industries and technologies that cause climate change than have developing nations in places such as Africa, Asia, the Caribbean Islands and the Pacific Islands which due to an unfortunate mixture of economic and geographic vulnerability, continue to shoulder the brunt of the burdens of climate change despite their relative innocence in causing it. The impacts of climate change including extreme flooding, intense droughts, rising sea levels, and unpredictable weather damage are more severe in developing countries resulting in both economic and non-economic loss and damage including loss of lives, damage to infrastructure and displacement of people.

Climate justice focuses on how climate change impacts people differently, unevenly and disproportionately and seeks to address the resultant injustices in fair and equitable way. The Loss and Damage has been hailed for recognizing the injustices caused by climate change whose impacts are more severe in developing countries. It has been described as a response to the climate injustice and climate debt, owed by the developed countries to the developing countries. It aims to help developing nations deal with loss and damage resulting from the effects of climate change.

The Loss and Damage Fund is therefore important in the climate finance agenda. It has been asserted that the establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund will add a third pillar to the global climate finance landscape which will now comprise of mitigation (funding to reduce emissions), adaptation (funding to minimize the negative impacts of emissions) and loss and damage (funding to address the harms caused by emissions). The Loss and Damage Fund will help vulnerable nations to rebuild the necessary physical and social infrastructure to deal with the negative consequences that arise from the unavoidable risks of climate change including rising sea levels, extreme heat waves, desertification, forest fires and crop failures. Further, it has been argued that the Loss and Damage Fund will help governments rebuild homes, hospitals and roads, avoid new debt burdens, and provide social protection to help communities bridge crises and avoid incidences of poverty after climate disasters.

The Loss and Damage Fund is therefore important since its establishment will expand the climate finance landscape. However, operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund is likely to face several hurdles. Among the key concerns is the ability of the Fund to meet the urgent and immediate need for new, additional, predictable and adequate financial resources while ensuring that existing development and climate financing for other priorities is not diverted. It has been argued that there is a real danger that the supposed ‘new and additional’ funding will not be new and additional at all since it will simply be drawn from existing aid budgets and taken from other areas thus hindering other climate change priority areas including mitigation and adaptation.

In addition, there are unresolved questions over who will provide finance and which countries will receive it. There have been suggestions that the Fund should be drawn from developed countries which have an obligation to fulfill their climate finance commitments in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities while others have suggested that there is need to find new, scaled up sources of funding such as innovative ‘polluter pays’ style instruments levied at a national level, such as a national carbon tax, and that high emitting industries could also contribute to the Fund.

It has been asserted there is no clarity over where the Loss and Damage Fund will be drawn from and how the Fund will be aligned with existing UNFCCC funds. It is further not clear whether all developing countries will be beneficiaries of the Fund or only those that are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. It is therefore imperative to define the scope of the Loss and Damage Fund in order to enhance its effectiveness. Finally, there are concerns over efficiency of the Loss and Damage Fund in providing much needed climate finance to countries affected by climate disasters.

Existing climate finance institutions and funds, such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, often have elaborate application processes, and take years to distribute funds. It has been argued that establishing the Fund under existing entities within the UNFCCC such as the Green Climate Fund is likely to encumber the Loss and Damage Fund with the institutional, legal, and procedural challenges that have plagued other existing funds and thus prevent vulnerable countries from expeditious access to funds needed to address loss and damage related to climate change. Further, it has also been argued that establishing the Fund as a new entity under the financial mechanisms of the UNFCCC will result in further fragmentation of the climate finance landscape.

The current environment of climate finance is now dispersed across dozens of multilateral and bilateral providers, each with their own requirements, procedures and processes a situation which places significant burden on vulnerable countries who find it difficult to access finance. It is therefore imperative to address the foregoing concerns in order to ensure the efficacy and efficiency of the Loss and Damage Fund and fulfill its objective of assisting developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in responding to loss and damage that arises from the impacts of climate change.

*This is an extract from the Book: Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2022 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Anderson. K., ‘What is the COP 27 Loss and Damage Fund?’ Available at https://greenly.earth/en-us/blog/company-guide/what-is-the-cop27-loss-anddamage-fund (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Climate Finance., ‘Climate Finance Essential for Mitigating and Adapting to Climate Change.’ Available at https://www.iberdrola.com/sustainability/what-is-climatefinance (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Giles. M., ‘The Principles of Climate Justice at CoP27.’ Available at https://earth.org/principlesofclimatejustice/#:~:text=That%20response%20should%20be%20based,the%20conse quences%20of%20clim ate%20change (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Hill. A.,& Babin. M ‘Why Climate Finance is Critical for Accelerating Global Action.’ Available at https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/why-climate-finance-critical-acceleratingglobal-action (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Hong. H., Karolyi. G. A., & Scheinkman. J.A., ‘Climate Finance.’ Review of Financial Studies, Volume 33, Issue 3 (2020).

Muigua. K., ‘Unlocking Climate Finance for Development.’ Available at https://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Unlocking-Climate-Finance-forDevelopment.pdf (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Paris Agreement., Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Reliefweb., ‘A Loss and Damage Fund: Two Big Challenges.’ Available at https://reliefweb.int/report/world/loss-and-damage-fund-two-big-challenges (Accessed on 18/09/2023).

Rumble. O, & Gilder. A., ‘Who, What, Where? The Loss and Damage Fund’s Unresolved Questions.’ https://africanarguments.org/2023/07/who-what-wherethe-loss-and-damage-funds-unresolved-questions/ (Accessed on 19/09/2023).

Sultana. F., ‘Critical Climate Justice’ Available at https://www.farhanasultana.com/wpcontent/uploads/Sultana-Critical-climatejustice.pdf (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

The London School of Economics and Political Science., ‘What is Climate Finance?’ Available at https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-climatefinance-and-where-will-itcomefrom/ (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

UNFCCC., ‘Decision -/CP.27 -/CMA.4: Funding Arrangements for Responding to Loss and Damage Associated with the Adverse Effects of Climate Change, Including a Focus on Addressing Loss and Damage.’ Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma4_auv_8f.pdf (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

United Nations Climate Change., ‘Introduction to Climate Finance.’ Available at https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

United Nations Climate Change., ‘Introduction to Climate Finance.’ Op Cit 9 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change., Available at https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/ application/pdf/con veng.pdf (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

United Nations Climate Change., ‘Loss and Damage.’ Available at https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/the-bigpicture/introduction#loss-and-damage (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

United Nations Climate Change., ‘Operationalization of the New Funding Arrangements, including a Fund, for Responding to Loss and Damage referred to in Paragraphs 2–3 of Decisions 2/CP.27 and 2/CMA.4.’ Available at https://unfccc.int/documents/636558 (Accessed on 25/11/2023).

United Nations Environment Programme., ‘What you Need to Know about the COP 27 Loss and Damage Fund.’ Available at https://www.unep.org/news-andstories/story/what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund (Accessed on 25/12/2023).

Wyns. A., ‘COP 27 Establishes Loss and Damage Fund to Respond to Human Cost of Climate Change.’ The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 7, Issue 1 (2023).

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

Uncategorized

Green and Sustainable Procurement in Kenya

Published

8 months agoon

February 13, 2024By

Admin

By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is The African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, The African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023) and Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024)*

Green and sustainable procurement is at the heart of the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development36. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 seeks to foster sustainable consumption and production patterns in all countries. One of the targets under SDG 12 is to promote public procurement practices which are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities. It has been argued that green and sustainable public procurement can influence the attainment of nearly all the SDGs. It can enhance the acquisition of green and sustainable products and services that are crucial in realizing the SDGs in areas such as food security, health, education, energy, clean water and sanitation, and infrastructure.

Green and sustainable public procurement can also positively influence SDG 13 (taking urgent action to combat climate change) by ensuring that environmental considerations such as energy and water efficiency are included in tenders for products or services. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), leveraging the enormous purchasing power wielded by public procurement, which is estimated to be 12% of GDP in developed countries and up to 30 % of GDP in developing countries, by promoting public procurement practices that are green and sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities, plays a key role in achieving Sustainable Consumption and Production (SDG 12) and in addressing the three pillars of Sustainable Development.

From an environmental perspective; sustainable procurement allows governments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve resource efficiency and support recycling; from a social dimension, the positive social results of green and sustainable procurement include poverty reduction, improved equity and respect for core labour standards; from an economic perspective, green and sustainable procurement can generate income, reduce costs, support the transfer of skills and technology and promote innovation by domestic producers. UNEP further asserts that shifting public spending towards more green and sustainable goods and services can help drive markets in the direction of innovation and sustainability, thereby enabling the transition to a green economy and achievement of the Sustainable Development agenda.

Green and sustainable public procurement is therefore integral in the sustainable development agenda. At the continental level, the Africa Union’s Agenda 2063 also embraces the role of green and sustainable procurement in the realization of the vision of an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the international arena. One of the key aspirations of Agenda 2063 is fostering environmentally sustainable and climate resilient economies and communities in Africa. Agenda 2063 identifies the need for sustainable consumption and production patterns in the realization of this aspiration and urges all African countries to develop and implement policies and standards including environmental laws and regulations and green procurement for sustainable production and consumption practices.

Promoting green and sustainable procurement is vital in the realization the vision of Agenda 2063. At the national level, the Constitution of Kenya enshrines Sustainable Development as one of the national values and principles of governance which binds all state organs, state officers, public officers and all persons. The Constitution therefore envisions the procurement process in Kenya to be guided by the principles of Sustainable Development. The Constitution further requires the procurement of public goods and services to be done in accordance with a system that is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective.

The Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act was enacted to give effect to Article 227 of the Constitution on procurement of public goods and services; to provide procedures for efficient public procurement and for assets disposal by public entities; and for connected purposes. The Act requires public procurement and asset disposal by state organs and public entities in Kenya to be guided by certain values and principles including the national values and principles provided for under Article 10 of the Constitution; maximisation of value for money; and promotion of local industry, Sustainable Development and protection of the environment. The Act therefore embraces the ideas of green and sustainable procurement by requiring environment and Sustainable Development considerations to guide the procurement process in Kenya.

In particular, the Act requires the procurement of public goods and services in Kenya to comply with specific requirements aimed at promoting green and sustainable procurement. It provides that an accounting officer of a procuring entity shall prepare specific requirements relating to the goods, works or services being procured that are clear, that give a correct and complete description of what is to be procured and that allow for fair and open competition among those who may wish to participate in the procurement proceedings. Such requirements include the need to factor in the socioeconomic impact of the goods, works and services; the need for goods, works and services to be environment-friendly; and cost effectiveness of goods, works and services.

In addition, the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Regulations also seek to promote green and sustainable procurement in Kenya. The Regulations require user departments in procurement entities while submitting requisitions to the head of the procurement function for processing, to ensure that the requisitions are accompanied by, inter alia, as applicable: environmental and social impact assessment reports. The Regulations further provide that the documents, procedures and approvals required for waste disposal management shall be obtained from the relevant public agencies allowing a procuring entity to dispose those items that are harmful and unfriendly to the environment.

It has correctly been pointed out that there is need for all public entities in Kenya to uphold the provisions of the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act and the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Regulations and work towards ensuring that both the processes of procurement of goods and disposal of waste are not only environmentally friendly but are also cost effective and contribute towards the realization of the Sustainable Development agenda in Kenya. Despite the appropriateness of green and sustainable procurement, it has been observed that the concept is yet to be fully embraced in developing countries like Kenya in both the private and public sectors.

It has been noted that the adoption of green and sustainable procurement in Kenya has been slow resulting in lower diffusion rate in Kenya. In addition, it has been argued that in as much as the government and other stakeholders may want to promote green and sustainable procurement in Kenya as demonstrated by the enactment of laws such as the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act, some organizations may be reluctant given that they see an opportunity in non-conformance. Organizations may shun away from green and sustainable procurement due to factors such as perceived added costs involved, poor management practices, poor policy communication, limited established environmental and sustainability criteria for products and services, lack of practical tools and information, and lack of clear interpretation of the concept of green and sustainable procurement.

There is need to promote green and sustainable procurement in Kenya in order to foster Sustainable Development. Green and sustainable public procurement also offers numerous benefits for both the public and private sector including enhanced economic performance, competitive advantage through innovation, improved public image, lower waste management costs, energy and resources conservation, and risk reduction among others.

*This is an extract from the Book: Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2022 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

Africa Union., ‘Agenda 2063: The Africa we Want.’ Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33126-docframework_document_book.pdf (Accessed on 21/12/2023).

Aggarwal. S., ‘Why Is Procurement Important in Business?.’ Available at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-procurement-important-business-sanjeevaggarwal/ (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

Anggraen. K., & Melgar. M., ‘Green Public Procurement for Sustainable Horticulture: A Policy Brief.’ Available at https://www.cscp.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/07/GOALAN_GPP_Policy_Brief.pdf (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Appolloni. A., ‘Green Procurement in the Private Sector: A State of the Art Review Between 1996 and 2013.’ Journal of Cleaner Production., (2014) 1-12.

Georgiev. N., ‘What is Procurement?: 4 Types of Procurement and Technology.’ Available at https://www.bluecart.com/blog/what-is-procurement (Accessed on 19/12/2023) 8 Emeritus., ‘Is Procurement Important? What are its Different Types? A Complete Guide.’ Available at https://emeritus.org/blog/finance-what-isprocurement/#:~:text=Procurement%20plays%20a%20 significant%20role,costs%20a nd%20minimizing%20financial%20risks. (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

Green Purchasing and the Supply Chain., Available at https://louisville.edu/purchasing/sustainability/greenpurchasingsupplychain (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Ho. L., Dickinson. N., & Chan. G., ‘Green Procurement in the Asian Public Sector and the Hong Kong Private Sector.’ Available at https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477- 8947.2010.01274.x (Accessed on 20/12/2023)

Jabbour. J et al., ‘How can Green Public Procurement Contribute to a More Sustainable Future.’ Available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/howcan-green-public-procurement-contribute-more-sustainable-future (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Large. R., Thomsen. C., ‘Drivers of Green Supply Management Performance: Evidence from Germany.’ Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management., Volume 17, Issue 3, (2011).

Maina. J., ‘State Should Set Good Example by Promoting Sustainable Procurement.’ Available at https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/amp/opinion/article/2001450226/state-shouldset-good-example-by-promoting-sustainable-procurement (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Mak. J., ‘What is Procurement?’ Available at http://www.rfpsolutions.ca/articles/Jon_Mak_IPPC6_What_is_Procurement_3Mar2014.pdf (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

National Library of Medicine., ‘Theories about Procurement and Supply Chain Management.’ Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK286086/ (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

Nordic Council of Ministers., ‘Sustainable Public Procurement and the Sustainable Development Goals.’ Available at https://norden.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:1554600/FULLTEXT01.pdf (Accessed on 21/12/2023).

Poliautre. D., ‘Green Procurement: A Guide for Local Government.’ Sustainable Energy for Environment & Development Programme., Volume 2, No. 10 (2012).

Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act, No. 33 of 2015, Laws of Kenya Government Printer, Nairobi

Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Regulations, 2020, Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 53 (Legislative Supplement No. 37), Legal Notice No. 69, Laws of Kenya.

Reich. A., ‘What Is Procurement? Types, Processes and Tech.’ Available at https://www.order.co/blog/procurement/define-procurement/ (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

SDG 12 Hub., ‘Roundtable on Sustainable Public Procurement as a Tool for Paris Agreement at COP 28.’ Available at https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/news-andevents/news/roundtable-sustainable-public-procurement-tool-paris-agreementcop28 (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Sustainable Procurement: Definition, State of Play and Advantages., Available at https://www.manutan.com/blog/en/glossary/sustainable-procurement-what-itmeans-the-state-of-play-and-the-advantages-itoffers#:~:text=Sustainable%20procurement%20refers%20to%20procurement, sustainable%20development%20and%20social%20responsibility. (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

United Nations Environment Programme., ‘Sustainable Public Procurement.’ Available at https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-wedo/sustainable-publicprocurement #:~:text=SPP%20Implementation%20Guidelines%3A%20UNEP%20has, of%20Sustainable%20Public%20 Procurement%20criteria. (Accessed on 21/12/2023).

United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards., ‘Scaling up Voluntary Sustainability Standards through Sustainable Public Procurement and Trade Policy.’ Available at https://unctad.org/system/files/officialdocument/unfss_4th_2020_en.pdf (Accessed on 19/12/2023).

United Nations General Assembly., ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.’ 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1., Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda %20for%20Sustain able%20Development%20web.pdf (Accessed 21/12/2023).

Walker. H., & Brammer. S., ‘Sustainable Procurement in the United Kingdom Public Sector.’ Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20190428091155id_/https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws /files/415713/2007-15.pdf (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

Walker. H., & Philips. W., ‘Sustainable Procurement: Emerging Issues.’ Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Helen-Walker5/publication/254959498_Sustainable_procure ment_Emerging_issues/links/54d9e9a80cf297 0e4e7d191f/Sustainable-procurement-Emerging-issues.pdf (Accessed on 20/12/2023).

World Trade Organization., ‘Government Procurement.’ Available at https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/edmmisc232add27_en.pdf (Accessed on 19/12/2023)

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

Uncategorized

Wanyama: Huduma Kiosks Reflection of Current LSK Lazy Approach

Published

9 months agoon

February 6, 2024By

Admin

Statement of Peter Wanyama, Advocate on Huduma Centre Judiciary Kiosks and Lazy LSK Approach:-

From the recent revelation, it is patently clear that LSK Council knew about the proposals to establish Huduma legal kiosks more than 1 year ago but was crassly negligent in addressing the issue and protecting practice. How can such a major development pass the leadership of the LSK ? Why call for public participation after the Huduma kiosks have already been set up ? The best solution NOW is to shut down those kiosks and FORCE the NCAJ and the Chief Justice to address concerns of practitioners.

On another note, the problem reflects a leadership deficit at LSK. Our practicing space is being encroached by non-qualified persons and yet our leaders are NOT aggressive enough. This hurts me to the core. Seems that our leaders at LSK and are more concerned about the quality of juice they take in Council meetings and can issue the CEO of LSK a Notice to Show Cause for refusal to carry a personal handbag- than aggressively pushing the concerns of practitioners and protecting.

I take the firm view that LSK leaders should be persons who are capable of assessing the entire policy and legal landscape, sometimes preemptively- to monitor risks to legal practice and doing what it takes to protect it. We must be aggressive in protecting practice the same way we push for the rule law and constitutionalism. Conceivably, you can’t demostrate in the streets to protect the rule of law when you are hungry. In sum, we need freshness at the LSK. I undertake to be your consequential, pushy, and strategic LSK President. I will lead a Council that protects practice without creating EXCUSES. Under my tenure- we wont accept anything that threatens practice.

THE WAY FORWARD ON HUDUMA KIOSKS

Huduma kiosks have now been implemented. The CJ says they soon be rolled out in all parts of Kenya. From a legal risk analysis- judges are likely to delay hearing any Petition challenging the Huduma kiosks because of the constitutional doctrine of access to justice as fortified in the Kituo Cha Sheria case yet the concerns of the practitioners are beyond this. Practitioners are concerned about the consequences of the implementation of the Huduma kiosks- especially them being potential fertile grounds that take away work from lawyers. Moreover, the kiosks will undoubtedly provide fodder for quacks, and clerks to practice law.

To me, we need tactics beyond litigation. Can we force the NCJA and CJ to halt the kiosks pending consultation with LSK members? At Kisumu, the Huduma center is not more than 400 meters away from the Law Courts- is this really about access to justice ? There are so many law courts in rural Kenya; why cant we establish Access- to- Justice- Shops in those law courts ? Where is the Concept Note that provides the rationale for these Huduma Kiosks ? Can it be shared with practitioners for input and feedback? Why the hurry to set up the Huduma kiosks ? What is really going on? I maintain, that we MUST shut down those kiosks until our concerns are addressed. Remember, this is a bread and butter issue. Let us not play around with our practicing space !

For more details: Peter Manyonge Wanyama [PMO] LSK Presidency 2024 Manifesto

Peter Manyonge Wanyama [ PMO]

LSK Presidential Candidate 2024.

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

- October 12, 2024

George Kashindi: Top Statesperson in Commercial Law in 2024

Josephine L.M. Righa: Hall of Fame Commercial Lawyer in 2024

Mwangi Kibicho: Top Statesperson in Commercial Law in 2024

Understanding the Legacy of Wealth: Intro to Transgenerational Estate Planning

The Unfolding Scenario of Digital Lending Regulation in Kenya

What is Carbon Markets?

Trending

-

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame | Kenya in 2023

-

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years agoThe Definition, Aspects and Theories of Development

-

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years agoThe Definition and Scope of Biodiversity

-

Lawyers1 year ago

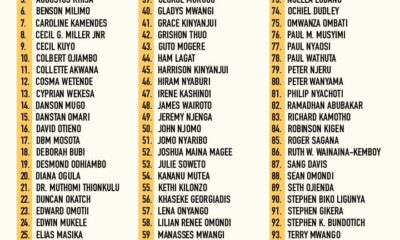

Lawyers1 year agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Top 100 Litigation Lawyers in Kenya 2023

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoTHE TOP 200 ARBITRATORS IN KENYA 2022

-

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year agoThe Role of NEMA in Pollution Control in Kenya

-

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years agoRole of Science and Technology in Environmental Management in Kenya

-

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year agoHow to Become an Arbitrator in Kenya