By Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD (Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Policy Advisor, Natural Resources Lawyer and Dispute Resolution Expert from Kenya), Winner of Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021, ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021*

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 recognises culture as the foundation of the nation and as the cumulative civilization of the Kenyan people and nation. In light of this, it obligates the State to, inter alia, promote all forms of national and cultural expression through literature, the arts, traditional celebrations, science, communication, information, mass media, publications, libraries and other cultural heritage; recognise the role of science and indigenous technologies in the development of the nation; and promote the intellectual property rights of the people of Kenya. Parliament is also obligated to enact legislation to: ensure that communities receive compensation or royalties for the use of their cultures and cultural heritage; and recognise and protect the ownership of indigenous seeds and plant varieties, their genetic and diverse characteristics and their use by the communities of Kenya.

The Ministry of Sports, Culture and Heritage was established through the Executive Order No. 2 “Organization of the Government of the Republic of Kenya dated May 2013” and comprises of departments of Sports, Office of the Sports Registrar, Culture, Permanent Presidential Music Commission, Kenya National Archives and Documentation Services, Library Services, Records Management, The Arts Services. Part of their mandate includes ‘developing, promoting and coordinating research, copyrights and conservation of Culture’ and to ‘develop, promote & coordinate the national culture policy, heritage policy and its management’. Notably, the core functions of the Department of Culture under the Ministry are: the promotion, revitalization and development of all aspects of culture- including performing, visual arts, languages indigenous health, nutrition, environment, and oral traditions; and, education, information and research on all aspects of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

The Department’s core mandate includes, to: advise the government on cultural matters; set policy standards to guide the development of cultural programmes; develop national cultural infrastructure and actively engage in the promotion, preservation and development of culture, in collaboration with other likeminded government agencies, County governments, and local communities based on the principles of Free Prior and Informed Consent; coordinate the documentation of national cultural inventories, and support cultural programmes and events; promote the use of Kiswahili, sign and indigenous languages in Kenya; coordinate safeguarding of Kenya’s intangible cultural heritage and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions; conduct capacity building for county governments, and disseminating cultural information; coordinate and facilitate cultural exchange programmes for groups and individuals; liaise with cultural offices and Offer technical support for cultural development programmes; and register cultural groups, associations and agencies.

Notably, the Department of Culture acknowledges that ‘while it has been playing some of the key roles in promotion of cultural integration, formulation of policies and standards that will guide the development of culture, Kenyan identity and social cohesion, both at the national and international levels, little information has been available to the Kenyan public’. However, while the Department, in line with its constitutional mandate, seeks to use its website to disseminate information, and open up an online forum, where all Kenyans can contribute towards realisation of our shared dreams and aspirations; our pride in ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity, and the determination to live in peace and unity, as one indivisible and sovereign nation, there are challenges that come with this.

Arguably, most of the custodians of the cultural practices and knowledge of Kenyan communities are either not able to access the internet due to infrastructure challenges or do not simply have the formal education required to enable them do so. This therefore means that the Department’s initiative, however well meaning, will either not reach a large section of the target group or will not benefit from added knowledge that would be gained from the input of elders from the villages. There may therefore, be a need for the Department to organize physical forums where they can meet the communities’ elders and leaders and share their dream with them in a bid to enrich their cultural knowledge database. The only way that the Department of culture and heritage can effectively achieve their mandate of advising the government on cultural matters, dissemination of cultural information, conducting capacity building for county governments, coordination and facilitate cultural exchange programmes for groups and individuals, offering technical support for cultural development programmes and registering cultural groups, associations and agencies would be through organizing forums where communities, without the limitation of technology or distance would come forward and share what they have with the Department.

This cannot certainly be the online platform. Physical meetings should thus be organized at the grassroots level. Through such forums, the Department can collaborate with the other stakeholders especially in matters that are relevant to the sustainable development agenda in order to tap into the communities’ knowledge and practices where such can help in promoting sustainability. Some of the main challenges that have been identified especially in relation to the implementation of the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in Kenya, in the past include; Lack of a coordinated national framework on implementation of the Convention; Lack of official cultural statistics that has negatively affected fiscal and political decisions; Inadequate legislative and institutional framework to promote the cultural and creative cultural sector; Inadequate cultural infrastructure and spaces for cultural expression; and Lack of awareness and non-appreciation on the role of culture in development by key policy makers.

Cultural expressions, services, goods and heritage sites can contribute to inclusive and sustainable economic development, thus making a vital contribution to eradication of poverty as envisaged under sustainable development goal 1 of the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development Goals. This is because the natural and environmental resources form the basis of the 2030 SDGs Agenda for provision of the resources required for eradication of poverty. These resources however require conservation for the sake of the current and future generations. It is also true that conservation principles and practices evolve and adapt to the cultural, political, social and economic environments in which they take place. It is for this reason that cultural practices of communities become critical in giving communities a chance to participate in sustainable development discourse. It has been observed that conservation practices are intimately linked to codes of ethics dictated by local and/or international systems of values. In turn, these values are inscribed in legal frameworks or they comply with legal texts.

Arguably, it is not enough for the laws in Kenya to acknowledge the place of communities’ cultural practices; there is a need to actually implement and incorporate these practices in environmental management and conservation measures through engaging communities in national plans and strategies geared towards the realisation of the sustainable development goals. Notably, while Kenya has been making progress towards realisation of the SDGs, if a 2017 Report by the Ministry of Devolution dubbed ‘Implementation of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development in Kenya is anything to go by, there is little evidence of incorporation of communities’ practices and indigenous knowledge in tackling the challenges that are likely to derail the realisation of the Agenda 2030. The process seems to be state-led, with communities playing a peripheral role. They only seem to be included in making peace, which in itself is critical for development, but that is just about all.

The farthest the Report has gone in demonstrating communities’ inclusion is ‘the Government putting in place mechanisms to foster peace among warring communities through initiatives like joint Cultural Festivals, and signing treaties on cultural exchange programmes with 51 countries hosting Kenya Missions’ in pursuit of SDG Goal 16 on ‘promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all level’. Thus, while there are admittedly policy, legal and institutional frameworks meant to promote the utilization of cultural and traditional community knowledge in national development, there is little evidence that the same is actively being pursued.

*This article is an extract from the Article: “Integrating Community Practices and Cultural Voices into the Sustainable Development Discourse,” (2021) Journal of Conflict Management and Sustainable Development Volume 6(2), p. 45 by Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya). Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a Senior Lecturer of Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law and The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP). He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Dr. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Africa Trustee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates. Dr. Muigua is recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2022.

References

Adom, D., ‘The Place and Voice of Local People, Culture, and Traditions: A Catalyst for Ecotourism Development in Rural Communities in Ghana’ (2019) 6 Scientific African e00184.

Anne-Marie Deisser and Mugwima Njuguna, Conservation of Cultural and Natural Heritage in Kenya (2016) 1 accessed 6 January 2021.

Cities U and Governments L, Culture in the Sustainable Development Goals: a Guide for Local Action (Academic Press 2015) accessed 3 January 2021.

Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2005, Paris, 20 October 2005.

Constitution of Kenya, 2010, Laws of Kenya, Government Printer, Nairobi.

Dessein, J. et al (ed), ‘Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development: Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability,’ (University of Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015), p. 14. Available at http://www.culturalsustainability.eu/conclusions.pdf (accessed 6 January 2021).

Harris J, ‘Basic Principles of Sustainable Development’ (2001).

Human Rights Watch, ‘Kenya: Abusive Evictions in Mau Forest’ (Human Rights Watch, 20 September 2019) https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/20/kenya-abusive-evictions-mau-forest (accessed 6 January 2021).

The Ministry of Sports, Culture and Heritage, ‘The Ministry,’ http://sportsheritage.go.ke/the-ministry/ (accessed 6 January 2021)..

Nocca F, ‘The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool’ (2017) 9 Sustainability 1882, 2 https://www.agbs.mu/media/sustainability-09-01882-v3.pdf (accessed 6 January 2021).

Republic of Kenya, Implementation of the Agenda 2030 For Sustainable Development in Kenya, June, 2017, 45 https://www.un.int/kenya/sites/www.un.int/files/Kenya/vnr_report_for_kenya.pdf (accessed 6 January 2021).

The Ngorongoro Declaration on Safeguarding African World Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Development, adopted in Ngorongoro, Tanzania on 4 June 2016.

UNDP, ‘Sustainable Development Goals | UNDP in Kenya’ (UNDP) https://www.ke.undp.org/content/ kenya/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed 6 January 2021).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), ‘Culture for Sustainable Development,’ available at http://en.unesco.org/themes/culture-sustainable-development Accessed 6 January 2021.

United Nations, Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, para. 36.

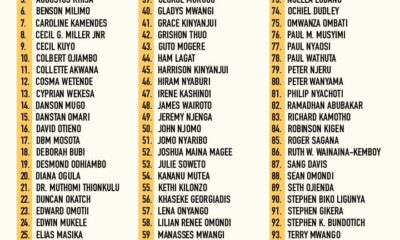

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago