By Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD (Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Policy Advisor, Natural Resources Lawyer and Dispute Resolution Expert from Kenya), Winner of Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021, ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021*

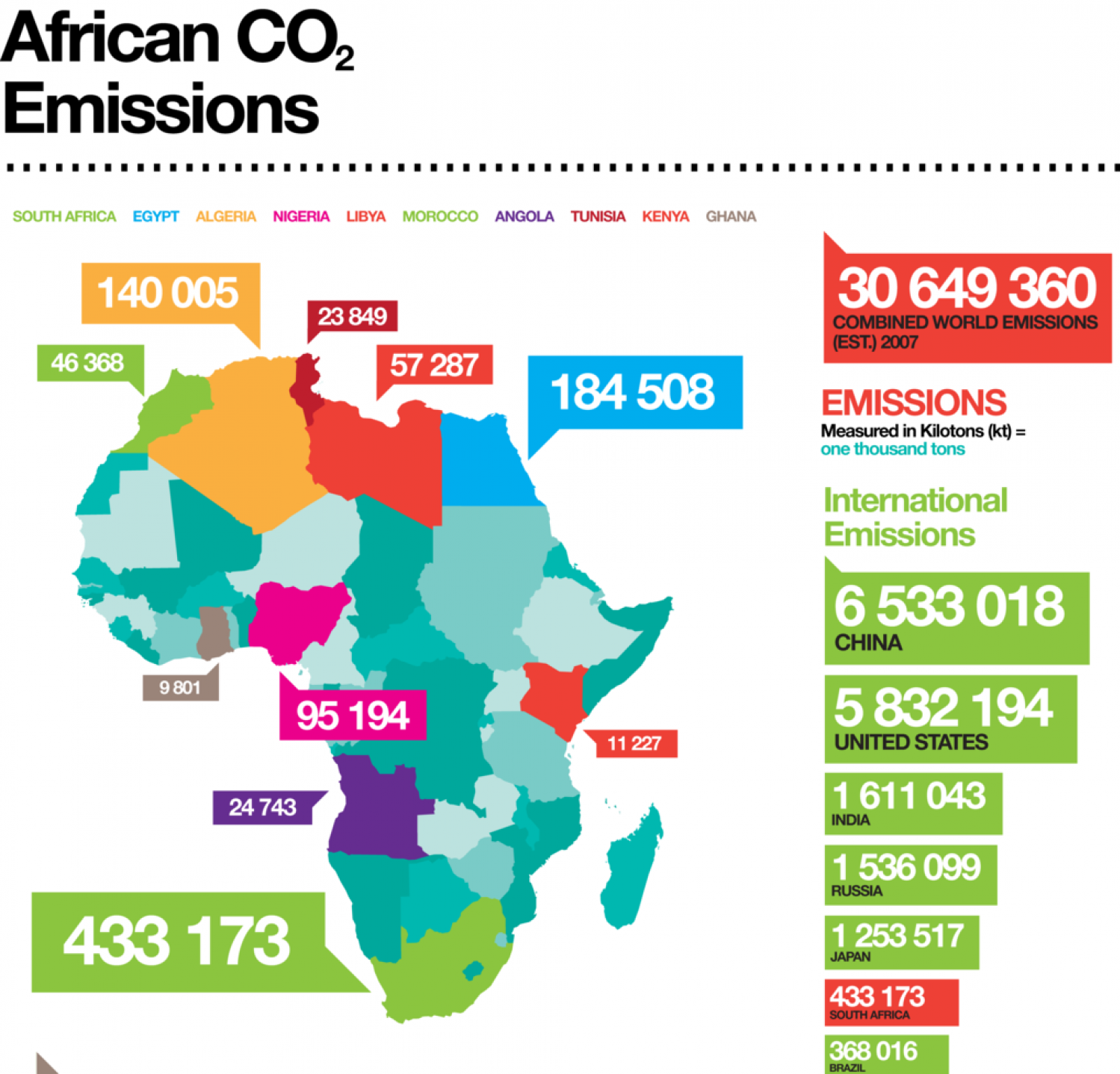

It is estimated that without new policies, by 2050, more disruptive climate change is likely to be locked in, with global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions projected to increase by 50%, primarily due to a 70% growth in energy-related CO2 emissions. The debate on what African countries can do reduce carbon emissions has largely been missing. In this article, in line with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities under the international environmental law, we discuss some of the viable steps African States to take to address to reduce carbon emissions and hasten the race to zero.

Clean Development Mechanism

Carbon or emissions trading works by limiting the amount of carbon dioxide that entities such as companies, municipalities or countries can release into the atmosphere, creating competition to encourage them to become more energy efficient and adopt cleaner technology whereby companies aiming to reduce their carbon output can sell unused pollution allowances and those that exceed their allocated emissions allowance may have to buy more emissions permits, or be subject to monetary fines. African countries should invest in and explore more clean development mechanisms not only as way of raising funds but also for climate change mitigation. For instance, Kenya has introduced the Green Bond Programme – Kenya, which aims to promote financial sector innovation by developing a domestic green bond market.

Transition to Electric Vehicles in Africa

Currently, the transport sector accounts for around a quarter of energy-related CO2 emissions globally since it is almost completely dependent on fossil fuels and, therefore, decarbonizing the sector is crucial to achieving the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement. Notably, in Africa and South Asia, the transition to low-carbon vehicles is vital in mitigating climate change. While improved and expanded physical infrastructure through investment in roads and rail lines is an important and necessary enabler of socio-economic development, countries must start moving towards environmental friendly means of transport such as electric vehicles, through financial incentives as has been witnessed in Rwanda where the country’s leadership has unveiled incentives meant to encourage the citizenry to embrace electric cars.

Enhancing the Role of the Private Sector in Reducing Emissions

The Paris Agreement underscores the important role of Non-State Actors (NSAs), particularly the private sector in the implementation of the key provisions the landmark Pact adopted in 2015, such as the Nationally Determined Contributions, adaptation, mitigation and finance. Arguably, in addition to top-down national or international policy instruments that aim to regulate the amount and flow of global emissions, the private sector is rising as a potent force for change. The private sector is an important player in creating innovative and technological solutions, as well as providing resources to meet global environmental challenges. For instance, private sector financing is necessary to complement public sector finance in realizing universal energy access in conjunction with renewable energy uptake, which is often prevented by high financing costs as a result of a range of technical, regulatory, financial and informational barriers and their associated investment risks. Indeed, research shows that ‘without significant additional investments and dedicated policies, the goal of total rural electrification and universal access to modern cooking fuels and stoves by 2030 is unachievable’.

Investing in Energy Technology Innovation in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Most rural area residents have relied on biomass fuels for long due to their relatively cheaper accessibility as lack of financial resources is a key barrier to access to energy in rural Africa. The combustion of biomass fuels in traditional stoves produces greenhouse gases and aerosols such as black carbon and the extensive use of biomass can also result in forest, land, and soil degradation, leading to net CO2 emissions. As part of reducing GHG emissions, understanding the influence of energy technology innovation in reducing a country’s greenhouse gas emissions requires a systematic review to characterize the existing system. There is a need for adoption and promotion of low carbon resilient development initiatives. Low-carbon resilience is an agenda that tackles reducing carbon emissions while simultaneously building climate resilience and supporting development in a supposed win-win policy agenda.

Promoting Sustainable Sources of Energy and Transport through Poverty Eradication

There is two-way relationship between the lack of access to adequate and affordable energy services and poverty. Often, people who lack access to cleaner and affordable energy are often trapped in a re-enforcing cycle of deprivation, lower incomes and the means to improve their living conditions and using expensive and unhealthy forms of energy that provide poor and/or unsafe services. Most people especially in developing world struggle with lack of access to clean energy in what is now commonly referred to as energy poverty defined by the World Economic Forum 2010 as the lack of access to sustainable modern energy services and products. Currently, there are 1.2 billion people who lack access to electricity and nearly 40 per cent of the people in the world lacking access to clean cooking fuels’. There is a need to continually invest in research and development of newer and cleaner technologies as well as understanding the distribution of current and future energy needs, if the African countries are to overcome energy poverty and also achieve zero emissions from energy sources. Addressing poverty can go a long way in empowering people to not only embrace but also afford alternative and sustainable sources of energy and transport.

Investing in Off-Grid and Mini-grid Energy Sources

The use of renewable energy for climate change mitigation is yet another approach African States should consider in tackling climate change. As it is, the most cost-effective way to expand household electricity access varies widely, within and between countries. Observers say that ‘in sub-Saharan Africa, two-thirds of the population live in areas that are not linked up with an electrical grid, and arguably, off-grid energy is the only option for these people. Hence, off-grid energy options are hailed as viable tools of combating energy poverty especially in Africa. Mini-grids are also considered to be a viable option for those living in the most remote areas, where standalone solar systems operating independently of the grid can meet smaller home electricity needs but may struggle with larger electricity loads such as powering machinery and agricultural equipment, and that is where mini grids which operate in a space between the two come in; when the population is too small or remote for grid extension and standalone solar systems aren’t viable for larger electricity needs. There is a need for continued exploration and investments in this sector to empower people regardless of their distance from the main national power grid.

*This article is an extract from the Article: “The Race to Zero Emissions from an African Perspective,” (2021) Journal of Conflict Management and Sustainable Development Volume 7(3), p. 1 by Dr. Kariuki Muigua, PhD, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya). Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Dr. Kariuki Muigua is a Senior Lecturer of Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law and The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP). He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Dr. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Africa Trustee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates. Dr. Muigua is recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2022.

References

Allet M, ‘Solar Loans through a Partnership Approach: Lessons from Africa’ [2016] Field Actions Science Reports, The Journal of Field Actions

Amesheva I, ‘The Road to Net-Zero Is Paved with Good Intentions’, https://www.arabesque.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-Road-to-NetZero_Part-One_FINAL.pdf> Accessed 24 September 2021.

Association GO-GL, ‘Providing Energy Access through Off-Grid Solar: Guidance for Governments’ [2015] Utrecht, the Netherlands, 9.

Cimate Change “Biggest Threat Modern Humans Have Ever Faced”, World Renowned Naturalist Tells Security Council, Calls for Greater Global Cooperation | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases’ https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sc14445.doc.htm accessed 23 September 2021.

Collett, Katherine A., Maximus Byamukama, Constance Crozier, and Malcolm McCulloch. “Energy and Transport in Africa and South Asia.” Energy and Economic Growth (2020), 2.

Collins Mwai, ‘Rwanda Unveils New Incentives to Drive Electric Vehicle Uptake’ (The New Times, Rwanda, 16 April 2021) https://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/rwanda-unveils-new-incentives-drive-electric-vehicle-uptake accessed 17 October 2021.

Environmental Migration Portal, ‘Accelerating SDG 7 Achievement: Policy Briefs in Support of the First SDG 7 Review at the UN High-Level Political Forum 2018’ Available at: https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/accelerating-sdg-7-achievement-policy-briefs-support-first-sdg-7-review-un-high-level-political (Accessed 12 October 2021).

González-Eguino, M., “Energy Poverty: An Overview.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47 (July 1, 2015): 377–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.013.

Green Finance Platform, ‘Achieving Clean Energy Access in Sub-Saharan Africa,’ (8 April 2019) https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/research/achieving-clean-energy-access-sub-saharan-africa (Accessed 12 October 2021).

GSDRC, ‘The Role of the Private Sector,’ Available at: https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/urban-governance/elements-of-effective-urban-governance/the-role-of-the-private-sector/(accessed 27 September 2021).

Green Bonds Kenya, ‘Kenya Green Bonds Programme,’ https://www.greenbondskenya.co.ke/(accessed 17 October 2021).

Habitat for Humanity, “Energy Poverty,” https://www.habitat.org/emea/about/what-we-do/residential-energy-efficiency[1]households/energy-poverty (Accessed October 12, 2021).

Jordaan, S.M., Romo-Rabago, E., McLeary, R., Reidy, L., Nazari, J. and Herremans, I.M., ‘The Role of Energy Technology Innovation in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Case Study of Canada’ (2017) 78 Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.

Karekezi, S. and others, ‘Energy, Poverty, and Development’ in Global Energy Assessment Writing Team (ed), Global Energy Assessment: Toward a Sustainable Future (Cambridge University Press 2012) 153 https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/global-energy-assessment/energy-poverty-and-development/DC1771AD93DD0A5031A07B057CA3A8C7 (Accessed 12 October 2021).

Năstase C and Popescu M, ‘Sustainable Development through the Resource Use[1]Regional Innovation System.’, Proceedings of the 3rd IASME/WSEAS International Conference on energy, environment, ecosystems and sustainable development (EEESD’07), Agios Nikolaos, Crete Island, Greece, 24-26 July, 2007 (World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press (WSEAS Press) 2007).

PACJA, ‘The role of the African private sector in the transition to low-emission, climate-resilient, green growth and NDCs implementation,’ 9th Conference On Climate Change and Development in Africa (CCDA-IX), Santa Maria, Sal Island, Cabo Verde, 13-17 September 2021.

Pachauri, Shonali, Bas J. van Ruijven, Yu Nagai, Keywan Riahi, Detlef P. van Vuuren, Abeeku Brew-Hammond, and Nebojsa Nakicenovic. “Pathways to Achieve Universal Household Access to Modern Energy by 2030.” Environmental Research Letters 8, no. 2 (May 2013): 024015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748- 9326/8/2/024015.

OECD, ‘Climate Change Chapter of the OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050: The Consequences of Inaction – OECD’ accessed 17 October 2021.

Shoibal, C. and Massimo, T., ‘Energy Poverty Alleviation and Climate Change Mitigation: Is There a Trade Off?’ (2013) 40 Energy Economics S67, S67. 88 González-Eguino, Mikel. “Energy Poverty: An Overview.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47 (July 1, 2015): 377–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.013.

Sun-Connect-News, ‘3 Reasons Off-Grid Solar Energy Isn’t Yet Serving the Poor in Sub-Saharan Africa,’ Available at: https://www.sun-connect-news.org/de/articles/market/details/3-reasons-off-grid-solar-energy-isnt-yet-serving-the-poor-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed 12 October 2021).

UNFCCC, ‘Advancing Electric Mobility in Africa,” available at: https://unfccc.int/news/advancing-electric-mobility-in-africaaccessed 13 October 2021.

UNEP, ‘Private Sector Engagement’ (2 June 2021) Available at: http://www.unep.org/about-un-environment/private-sector-engagementaccessed 27 September 2021.

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago