By Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, C.Arb, FCIArb is a Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution at the University of Nairobi, Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration, Leading Environmental Law Scholar, Respected Sustainable Development Policy Advisor, Top Natural Resources Lawyer, Highly-Regarded Dispute Resolution Expert and Awardee of the Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) of Kenya by H.E. the President of Republic of Kenya. He is the Academic Champion of ADR 2024, the African ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, the African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, ADR Practitioner of the Year in Kenya 2021, CIArb (Kenya) Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 and ADR Publisher of the Year 2021 and Author of the Kenya’s First ESG Book: Embracing Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) tenets for Sustainable Development” (Glenwood, Nairobi, July 2023) and Kenya’s First Two Climate Change Law Book: Combating Climate Change for Sustainability (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Achieving Climate Justice for Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, October 2023), Promoting Rule of Law for Sustainable Development (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) and Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024)*

ESG are increasingly driving corporate respect for human rights. It has been observed that as companies increasingly recognize the reputational and financial risks of adverse human rights impacts, corporate human rights commitments and due diligence practices have become more prevalent. The relationship between human rights and corporate sustainability practices is recognized under the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Agenda represents a shared blue print for peace and prosperity for people and the planet in the quest towards the ideal of Sustainable Development.

The Agenda envisions attainment of the ideal of Sustainable Development through 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which seek to strike a balance between social, economic and environmental facets of sustainability. It has been argued that human rights and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are inextricably linked. The 2030 Agenda is explicitly grounded in international human rights. It has been asserted that the 17 SDGs seek to realize the human rights of all, and more than 90% of the targets directly reflect elements of international human rights and labour standards.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide a framework for realizing Environmental, Social and Governance standards within the human rights framework by enshrining the corporate responsibility to respect human rights. They are the world’s most authoritative, normative framework guiding responsible business conduct and addressing human rights abuses in business operations and global supply chains.

The Principles are grounded in recognition of States’ existing obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights and fundamental freedoms; the role of business enterprises as specialized organs of society performing specialized functions, required to comply with all applicable laws and to respect human rights; and the need for rights and obligations to be matched to appropriate and effective remedies when breached.

Among the fundamental principles under the framework is that business enterprises should respect human rights. This means that they should avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved. Embracing the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights can therefore promote corporate respect for human rights under the ESG agenda.

In addition, The Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration flow from the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and provide a framework through which business entities can be compelled to comply with ESG standards through arbitration. Further, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct are recommendations jointly addressed by governments to multinational enterprises to enhance the business contribution to Sustainable Development and address adverse impacts associated with business activities on people, planet, and society.

The Guidelines provide that Multinational Enterprises should respect the internationally recognised human rights of those affected by their activities. They further urge Multinational Enterprises to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts and address such impacts when they occur; seek ways to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their business operations, products or services by a business relationship, even if they do not contribute to those impacts; have a publicly available policy commitment to respect human rights; carry out human rights due diligence as appropriate to their size, the nature and context of operations and the severity of the risks of adverse human rights impacts; and provide for or co-operate through legitimate processes in the remediation of adverse human rights impacts where they identify that they have caused or contributed to these impacts.

One of the key goals of ESG is to foster sustainable, responsible or ethical investments. The OECD Guidelines can help Multinational Enterprises achieve this goal by integrating human rights due diligence in their investment practices. Further, the International Labour Organization (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work seeks to foster respect for fundamental human rights and freedoms at work.

The ILO Declaration stipulates that in seeking to maintain the link between social progress and economic growth, the guarantee of fundamental principles and rights at work is of particular significance in that it enables the persons concerned to claim freely and on the basis of equality of opportunity their fair share of the wealth which they have helped to generate, and to achieve fully their human potential.

It sets out fundamental human rights and freedoms that should be upheld by all persons including states and businesses among them being the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour; the effective abolition of child labour; the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; and a safe and healthy working environment.

The ILO Declaration is an expression of commitment by governments, employers’ and workers’ organizations to uphold basic human rights and values that are vital to social and economic lives. At a continental level, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights through its Resolution on Business and Human Rights in Africa states that respect for human rights norms and principles by business enterprises in the countries of operation is a prerequisite for the Sustainable Development envisaged in African Union’s Agenda 2063.

The Resolution seeks to foster effective domestication of applicable regional human rights standards on business and human rights and the development of mechanisms for their effective implementation. It urges Africa to embrace a human rights-based approach to development.

At a national level, the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) ESG Disclosures Guidance Manual encourages listed companies to assess impact of ESG issues to their organisations (such as climate change and human rights) in addition to their organisations own ESG impacts to society (such as material resource use and emissions) when determining material ESG impacts for disclosure. It requires listed companies to report on several ESG issues including their impacts on human rights, and how they manage these impacts. The NSE Disclosures Guidance Manual is therefore important in enhancing respect for human rights by listed companies in Kenya by requiring them to report on their human rights practices in their ESG Disclosures.

From the foregoing, it emerges that human rights are well placed within the ESG framework at the global, continental and national levels. However, it has been pointed out that some corporations fail to connect human rights standards and processes with ESG criteria and investment practices because of a prevailing lack of understanding on how human rights issues should be reflected in social criteria, environmental and governance indicators.

In addition, it has been contended that in most instances where human rights are considered in the ESG framework, they are limited to the ‘S’ tenet of ESG and not incorporated in other factors. Further, it has been argued that the human rights criteria adopted by most companies is limited to addressing climate change, advancing diversity and safety in the workplace, and striving for ethical supply chains. It has been pointed out that while these issues are critically important, they do not reflect the full spectrum of human rights.

As a result of the foregoing, it has been contended that ESG as a framework does not sufficiently capture harms to people (and resulting risk to business) or guide decisions that take human rights into account. Further, it has been argued that ESG can easily fail to identify and address notable human rights harms. It is therefore necessary to embrace human rights within the ESG framework in order to foster sustainability.

*This is an extract from Kenya’s First Clean and Healthy Environment Book: Actualizing the Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment (Glenwood, Nairobi, January 2024) by Hon. Prof. Kariuki Muigua, OGW, PhD, Professor of Environmental Law and Dispute Resolution, Senior Advocate of Kenya, Chartered Arbitrator, Kenya’s ADR Practitioner of the Year 2021 (Nairobi Legal Awards), ADR Lifetime Achievement Award 2021 (CIArb Kenya), African Arbitrator of the Year 2022, Africa ADR Practitioner of the Year 2022, Member of National Environment Tribunal (NET) Emeritus (2017 to 2023) and Member of Permanent Court of Arbitration nominated by Republic of Kenya and Academic Champion of ADR 2024. Prof. Kariuki Muigua is a foremost Environmental Law and Natural Resources Lawyer and Scholar, Sustainable Development Advocate and Conflict Management Expert in Kenya. Prof. Kariuki Muigua teaches Environmental Law and Dispute resolution at the University of Nairobi School of Law, The Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) and Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies. He has published numerous books and articles on Environmental Law, Environmental Justice Conflict Management, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Sustainable Development. Prof. Muigua is also a Chartered Arbitrator, an Accredited Mediator, the Managing Partner of Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates and Africa Trustee Emeritus of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators 2019-2022. Prof. Muigua is a 2023 recipient of President of the Republic of Kenya Order of Grand Warrior (OGW) Award for his service to the Nation as a Distinguished Expert, Academic and Scholar in Dispute Resolution and recognized among the top 5 leading lawyers and dispute resolution experts in Band 1 in Kenya by the Chambers Global Guide 2024 and was listed in the Inaugural THE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame 2023 as one of the Top 50 Most Distinguished Litigation Lawyers in Kenya and the Top Arbitrator in Kenya in 2023.

References

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights., ‘Resolution on Business and Human Rights in Africa’ -ACHPR/Res.550 (LXXIV), 2023.

African Union., ‘African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.’ Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36390-treaty-0011_- _african_charter_on_human _and_peoples_rights_e.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Ahmad. H., Yaqub. M., & Lee. S. H., ‘Environmental-, Social-, and GovernanceRelated Factors for Business Investment and Sustainability: A Scientometric Review of Global Trends.’ Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668- 023-02921-x (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Barbosa. A et al., ‘Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria: Their Impacts on Corporate Sustainability Performance.’ Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 410 (2023). Available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01919-0 (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Boyle. A., ‘Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next’ The European Journal of International Law, Vol. 23, No. 3.

British Business Bank., ‘What is ESG – A Guide for Businesses.’ Available at https://www.british-business-bank.co.uk/finance-hub/businessguidance/sustainability/what-is-esg-a-guide-for-smaller-businesses/ (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre., ‘Commentary: Human Rights are not Just an ESG Factor’ Available at https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latestnews/commentary-human-rights-are-not-just-an-esg-factor/ (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Cedric.R., ‘Accountability of Multinational Corporations for Human Rights Abuses.” Utrecht Law Review 14.2 (2018): 1-5.’

Constitution of Kenya., 2010., Government Printer, Nairobi.

Ethical Trading Initiative., ‘Human Rights Due Diligence.’ Available at https://www.ethicaltrade.org/insights/issues/human-rights-due-diligence (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Feldman. D., Mkhize. M., & Edmonds-Camara. H., ‘2023 African Forum on Business and Human Rights: What do companies need to know?.’ Available at https://www.globalpolicywatch.com/2023/09/2023-african-forum-on-businessand-human-rights-what-do-companies-need-to-know/ (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Flacks. M., & Norman. H., ‘What Does the ESG Backlash Mean for Human Rights?’ Available at https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-does-esg-backlash-mean-humanrights (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance., ‘Human Rights Due Diligence.’ Available at https://www.securityhumanrightshub.org/toolkit/factsheets/humanrights-due-diligence.html (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Global Campus of Human Rights., ‘Rethinking Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Investing for Successful Sustainability and Human Rights.’ Available at https://gchumanrights.org/gc-preparedness/preparednessdevelopment/article-detail/rethinking-environmental-social-and-governance-esginvesting-for-successful-sustainability-and-human-rights-5039.html (Accessed on 24/01/2024)

Henisz. W, Koller. T, & Nuttall. R., ‘Five Ways that ESG Creates Value.’ McKinsey Quarterly, 2019

International Labour Organization., ‘Business and the Labour Dimension of Human Rights Due Diligence.’ Available at https://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/businesshelpdesk/WCMS_867782/lang–en/index.htm (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

International Labour Organization., ‘Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.’ Available at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/— ed_norm/—declaration/documents/normative instrument/wcms_716594.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Kemp. B et al., ‘The Rise of ESG Litigation and Horizontal Human Rights Enforcement.’ Available at https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=07a94453-f2aa-490a-a7e1- f6c25256cbf9 (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Khobe. W., ‘The Horizontal Application of the Bill of the Rights and the Development of the Law to give Effect to Rights and Fundamental Freedoms’ (2014) 1, Journal of Law and Ethics.

Mathis. S., ‘Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG).’ Available at https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/environmental-social-andgovernance-ESG (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Matu. D., ‘Improving Access to Justice in Kenya through Horizontal Application of the Bill of Rights and Judicial Review’ Available at https://press.strathmore.edu/uploads/journals/strathmore-lawreview/SLR2/2SLR1_Article_4.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Mikhaeel. M., ‘How Human Rights Due Diligence Affects the ‘E’ in ESG.’ Available at https://www.financierworldwide.com/how-human-rights-due-diligence-affectsthe-e-in-esg (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Munoz. P., ‘Bridging the Human Rights Gap in ESG.’ Available at https://www.bsr.org/en/blog/bridging-the-human-rights-gap-in-esg (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Nairobi Securities Exchange., ‘ESG Disclosures Guidance Manual.’ Available at https://www.nse.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/NSE-ESG-Disclosures-GuidanceManual.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights., ‘Corporate Human Rights Due Diligence – Identifying and Leveraging Emerging Practices.’ Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/wg-business/corporate-humanrights-due-diligence-identifying-and-leveraging-emergingpractices#:~:text= The%20prevention%20of%20adverse%20impacts,people%2C%20n ot%20risks%20to%20business (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights., ‘Investors, ESG and Human Rights.’ Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/calls-for-input/2023/investorsesg-and-human-rights (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights., ‘Investors, ESG and Human Rights.’ Op Cit 89 Ibid 90 Rydzak. J., ‘ESG Data Needs a Human Rights Upgrade.’ Available at https://rankingdigitalrights.org/mini-report/esg-data-needs-a-human-rightsupgrade/#:~:text=ESG%20scores%20ignore%20human%20rights ,strive%20for%20et hical%20supply%20chains (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights., ‘What are Human Rights.’ Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/what-are-human-rights (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)., ‘Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct’ Available at https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100514804.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024)

Peterdy. K., & Miller. N., ‘What is ESG?’ Available at https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/esg/esg-environmental-socialgovernance/ (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

Simmons & Simmons., ‘Human Rights Due Diligence as Part of ‘Social’ in ESG.’ Available at https://www.simmonssimmons.com/en/publications/ckkce2jhz1nwg09857iumkfpb/human-rights-duediligence-as-part-of-social-in-esg (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Stuart. L.G et al., ‘Firms and Social Responsibility: A Review of ESG and CSR Research in Corporate Finance.’ Journal of Corporate Finance 66 (2021): 101889 10 Li. T., et al., ‘ESG: Research Progress and Future Prospects.’ Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0dd4/941ebea33330210daff5f37a1c8cdd0547d7.pd f (Accessed on 23/01/2024).

The Danish Institute for Human Rights., ‘Integrated Review and Reporting on SDGs and Human Rights.’ Available at https://sdghelpdesk.unescap.org/sites/default/files/2019- 07/integrated_review.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

The East African Centre for Human Rights., ‘A compendium on economic and social rights cases under the Constitution of Kenya, 2010’ available at https://eachrights.or.ke/wpcontent/uploads/2020/07/A_Compendium_On_Economic_And_Social_Rights_Cas es_Under_The_Constitution_Of_Kenya_2010.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

The Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration., Available at https://www.cilc.nl/cms/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/The-Hague-Rules-onBusiness-and-HumanRights-Arbitration_CILC-digital-version.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework., Available at https://www.ungpreporting.org/wpcontent/uploads/UNGPReportingFramework_2017.pdf (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

United Nations General Assembly., ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.’ 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1., Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda %20for%20Sustainabl e%20Development%20web.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights., Available at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinc iplesbusinesshr_en.p df (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights., Op Cit 123 European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive., Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464 (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

United Nations, Charter of the United Nations, 24 October 1945, 1 UNTS XVI.

United Nations., ‘Human Rights.’ Available at https://www.un.org/en/globalissues/humanrights#:~:text=International%20Human%20Rights%20Law&text=The%20United%20 Nations%20has%20defined,in%20carrying%20out%20their%20responsibilities. (Accessed on 24/01/2024)

United Nations., ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.’ Available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/treaties/1976/03/19760323%2006- 17%20am/ch_iv_04.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

United Nations., ‘International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.’ Available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/treaties/1976/01/19760103%2009- 57%20pm/ch_iv_03.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

Universal Declaration of Human Rights., Available at https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

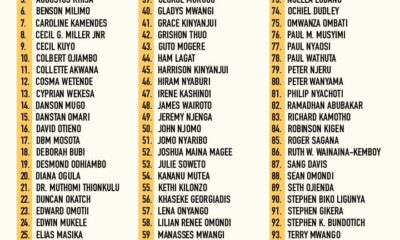

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis3 years ago

News & Analysis1 year ago

News & Analysis1 year ago