News & Analysis

Legal Instruments Relating to Gender Equality and Mainstreaming in Africa

News & Analysis

What is Carbon Markets?

As one of the top law firms in Nairobi, MMA Advocates is renowned for its proactive strategy and innovative legal lawyer advice. Our firm is committed to delivering strategic assistance that not only tackles current difficulties but also equips clients for future legal trends and advancements. As top lawyers in Nairobi Kenya, we take great satisfaction in our ability to combine in-depth legal knowledge with creative problem-solving. We keep a close eye on business trends and legal advancements to deliver timely guidance that enables our clients to make wise choices.

Our main goal as MMA Advocates is to establish long-lasting partnerships based on integrity, decency, and reliability. Since every client’s circumstance is unique, our best advocates in Kenya offer timely service and individualized attention at every stage of our collaboration. We make sure our clients are informed and empowered throughout their legal journey because we value openness and transparency in communication. In every case we take on, we are deeply committed to obtaining positive results and client satisfaction. This is just one aspect of our unwavering commitment to quality.

Whether you are a startup negotiating regulatory obstacles, an established corporation expanding, or a private citizen seeking legal assistance on personal problems, our Best Corporate Lawyers in Kenya are dedicated to becoming your legal partner. Our expertise include Commercial Litigation, Real Estate & Development, Fintech, Public Procurement (Public Private Partnerships), Project Finance, Public Law Litigation, Legal Audits & Compliance Advisory and Crisis Management.

We hope to arm you with the legal know-how and strategies needed to achieve your objectives. Our team enjoys taking on challenging legal matters with creativity and strategic understanding, protecting your rights and effectively achieving your goals. With a thorough comprehension of both regional laws and global norms, we are prepared to confidently and competently lead you through the complexities of corporate law.

In the intensely competitive legal arena, our tailored legal and strategic solutions distinguish us. We value depth over breadth, guaranteeing our clients our full dedication and unparalleled efficiency. Where many spread themselves wide, we narrow our focus to a select few of the most challenging cases. We tread the path less traveled.

To find out more about how MMA Advocates in Nairobi Kenya can help you with your legal issues, get in touch with us. With our team of committed professionals and our standing as one of the top law firms in Nairobi, we are well-positioned to offer outcomes that surpass expectations and guarantee your success in a legal environment that is always changing.

News & Analysis

Review: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Journal, Volume 12(3), 2024

Kariuki Muigua & Company Advocates is a Top-Tier Kenyan law firm situated at the heart of Nairobi city in Kenya. We are a broad-based practice with a reputation for offering a full range of quality services to our domestic and international clients.

At KM&CO, we take pride in offering personalized attention to our diverse clientele. Our practice aspires to offer efficient and cost-effective legal solutions that meet our esteemed clients’ needs in a timely and competent manner.

KM&CO was founded in 1993 by the current senior Advocate, Dr. Kariuki Muigua. It is based in the Central Business District of Nairobi at the Pioneer Assurance House located opposite 7th August Bomb Blast Memorial Park enjoying the convenience of close proximity to major financial, commercial and governmental institutions.

We are open for consultations with our clients worldwide; we have lawyers on standby for 24 hours to cover diverse time zones that impact on our global clients.

News & Analysis

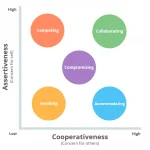

Way Forward in Applying Collaborative Approaches Towards Conflict Management

Kariuki Muigua & Company Advocates is a Top-Tier Kenyan law firm situated at the heart of Nairobi city in Kenya. We are a broad-based practice with a reputation for offering a full range of quality services to our domestic and international clients.

At KM&CO, we take pride in offering personalized attention to our diverse clientele. Our practice aspires to offer efficient and cost-effective legal solutions that meet our esteemed clients’ needs in a timely and competent manner.

KM&CO was founded in 1993 by the current senior Advocate, Dr. Kariuki Muigua. It is based in the Central Business District of Nairobi at the Pioneer Assurance House located opposite 7th August Bomb Blast Memorial Park enjoying the convenience of close proximity to major financial, commercial and governmental institutions.

We are open for consultations with our clients worldwide; we have lawyers on standby for 24 hours to cover diverse time zones that impact on our global clients.

-

Lawyers1 year ago

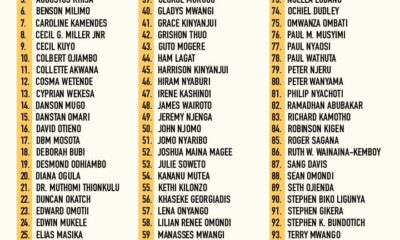

Lawyers1 year agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Litigation Hall of Fame | Kenya in 2023

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoThe Definition, Aspects and Theories of Development

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoThe Definition and Scope of Biodiversity

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoTHE TOP 200 ARBITRATORS IN KENYA 2022

-

News & Analysis10 months ago

News & Analysis10 months agoThe Role of NEMA in Pollution Control in Kenya

-

Lawyers1 year ago

Lawyers1 year agoTHE LAWYER AFRICA Top 100 Litigation Lawyers in Kenya 2023

-

News & Analysis2 years ago

News & Analysis2 years agoRole of Science and Technology in Environmental Management in Kenya

-

News & Analysis10 months ago

News & Analysis10 months agoHow to Become an Arbitrator in Kenya